The History of the Electric Car: Joy Riding in a Time Machine

Electric Vehicles (EV) have a long, dramatic history even before modern day tax credits and the quest for sustainability in our world.

They were efficient, beautiful machines. When production peaked in 1912 with over 30,000 electric cars on the road, battery operated vehicles seemed to be the way of the future. Upscale drivers had owned electrics for over a decade by then and the elegant electric automobiles were considered the most luxurious way to travel within a 100-mile range, or even as far as 240 miles as some claimed, between charging stations.

These high-tech automobiles from the turn-of-the-last century drove without a sound, because there were no vibrations from a rumbling motor. They were considered maintenance free. There were no gassy odors nor emissions since they were battery operated.

Automobiles with gasoline powered engines also had gas head and tail lamps that were lit by hand with a flaming match. In contrast, battery operated cars had glowing electrical lighting both inside and out that. Electric cars also did not require the rough handling involved with shifting gears. Their speed was regulated by the gentle push and pull on a tiller, instead of a steering wheel. It was officially called the “steering rod.”

Perhaps the essential attraction to electric cars was the elegant ease of the starter. Driver and passengers would slide into the sumptuous seats, and then, with a simple twist of a key or nudge against button and switch, off they’d go.

Unlike electrics in 1912, gasoline motored vehicles were difficult, and often dangerous, to start. Ample physical strength was required to crank the starter and it was essential to have a clear understanding of just how to adjust the choke at the same time. Gas powered engines would often backfire unexpectedly, causing the crank’s iron handle to kick back violently in the opposite direction. Broken thumbs, arms and dislocated shoulders were common injuries attributed to hand-cranked starters.

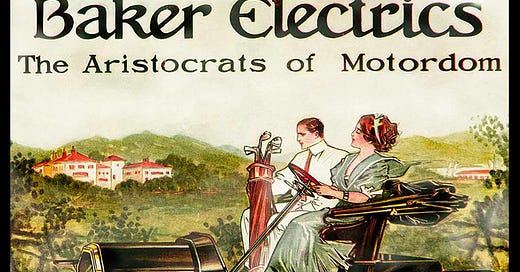

Electric cars traveled best over paved streets and this made the vehicles all the more appealing to professionals who lived and worked in urban areas. Baker Electric advertisements advised that their cars were well-suited for traveling in cities and towns, and popular vehicles for the professional uses of men, but especially, also for the social uses of women. New York City even commissioned a large fleet of elegant electric taxicabs available for those very reasons, with charging stations installed about every 10 blocks.

The automobiles were considered not only safe for women drivers and their families but they became exceedingly fashionable to own. Companies targeted their advertising campaigns through chic fashion magazines such as Vogue, Ladies Home Companion and The Designer with beautiful illustrations depicting refined, well-to-do woman with children traveling peacefully by electric auto to their most important social events or for elegant shopping excursions.

By the turn-of-the-last-century, Baker Electric Motor-Vehicle Company was the leading electric car manufacturer in the United States. Magazine and newspaper advertisements featured a long list of showrooms where Walter C. Baker’s fully electric, battery-operated cars and trucks were sold. Showrooms were located in Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, Denver, Memphis, Cincinnati as well as Decatur, Illinois. Westward expansion was planned to Seattle and other cities throughout the United States that year, especially promoting their new line of “Commercial Vehicles for every purpose.”

Out of the many competing electric car companies at the time, Walter C. Baker’s cars were especially sumptuous. One of his most exclusive models in 1912, the Baker Special Extension Coupe, had a starting price of $2700. This coupe was as tall as it was long, with sleek patent leather fenders tailored “fully skirted to the body.” Passengers rode high off the ground in regal fashion, enjoying panoramic views framed by beautifully arched, curtained windows that surrounded the interior of the automobile.

The most lavish electric cars were custom designed to the buyer’s specifications. Choices included colorful, velvety soft leather seats. Or, one could choose from an expensive catalogue of sumptuous imported fabrics for the fully upholstered interiors. Both seating and walls inside the vehicle were typically tufted, tasseled, and trimmed in rich brocades and satins against sparkling, ornate hardware. A showy clock and opulent cut-crystal flower vases were attached to the walls, softly lit by an overhead electric dome light. A mirrored “toilet case” or vanity was built into the interior design where passengers could touch up their hair, adjust their hat, or add a puff of powder to their cheeks before leaving the vehicle.

Baker’s 1912 catalogue was 24-pages long and in that, he carefully described and illustrated each car. He stated that the automobiles’ batteries were: 30 cells 11 M. V. Hycap-Exide. Ironclad-Exide at extra cost” and wrote: “It is not unusual for a Baker Electric to make 100 miles on a single charge, which is a very considerable distance for any town car or suburban vehicle. In the hands of expert drivers, a Baker Electric Victoria has been driven 244 miles on a single charge, establishing thereby the World’s Record.”

Although Baker’s Stanhope model sold for as little as $1000, the masculine, open- topped Runabout coupe was priced at $2000. The latter was described as a “racy model designed for the professional business man who wants more speed and mileage than the ordinary electric affords.”

At the top of the high-end Baker production line was the Baker Extension Brougham, and it was by far the most expensive of all. The car was marketed as a “five passenger vehicle, all facing forward, therefore permitting an unobstructed view for the driver.”

Designed for wealthy families, the Brougham came in black with blue, green or maroon exterior panels, and with the unique feature that both the driver and front passenger seats were made to swivel in any direction to accommodate the ostentatious clothing designs commonly worn at the time. The swivel seating was “ingeniously arranged for the most convenient entrance and egress.”

A Brougham had a starting price at $3500 before any of the lavish interior customizations. This was exceptionally expensive during this year when the 1912 Bureau of Labor Statistics recorded the annual salary of a school teacher at $507 and an attorney’s average yearly income at $1092.

The Fastest Vehicle

It all started in 1897, and the man was only 29 years old, when Walter C. Baker began his car company in Cleveland, Ohio. Within those first few years, Baker had designed the fastest, fully electric racing car destined to draw the public’s attention to his work in the electrics automotive field.

Designed for speed, The Road Torpedo, had an apposite name based on its aerodynamic and sharply elliptical fuselage. The race car almost fully encapsulated its driver and the electrician, who also worked the brakes, within its interior. The engine was powered by Thomas Edison’s batteries (and in fact, no surprise, Edison’s first automobile was a Baker Electric).

The Road Torpedo was the first car to successfully break the 100 mph land speed records during several initial test runs along Ormond Beach, Florida in early 1902. It was during the very final run when Baker claimed to have reached 127 mph, but the racing car crashed when its wheels fell off.

A few months later, Walter Baker went on to test his most powerful racing version of The Torpedo on Staten Island. He hoped to officially achieve the land speed record against all the other gasoline-powered autos that were involved with this race, and prove to the general public that electric vehicles were safe, sophisticated, and the way of the future.

The Infamous Race

A street course was laid out by the Automobile Club of America and the local Staten Island aldermen. This public event was scheduled over Memorial Day weekend with the intent to draw a tremendous crowd to witness this historic competition between the most technologically advanced automobiles of the time, as they competed over city streets at unheard of speeds.

According to the Richmond Co. Advance newspaper, published the following week, thousands of people lined what is now called Hylan Boulevard. The roadway ran through a somewhat rural section of Staten Island, not far from the beach, but also where two tourist hotels were conveniently located. The course included a few turns and an uphill section. Spotting stages were set up along the way, where officials clocked the individual cars with stopwatches.

The newspaper described Baker’s wooden racing car as “a curious-looking affair, built entirely for speeding purposes, and propelled by electricity. The lower part of the ‘auto’ consists of a regular horseless carriage frame, upon which is placed the storage batteries used for furnishing the power, while the upper part is built similar to a torpedo boat.”

The reporter went on to label the 3100 lb. electric Torpedo a “freak” but complimented the power Baker managed to achieve over the majority of the course. Then, according to eye-witnesses, something terrible happened within 220 yards of the finish line.

A Tragic Accident

The Torpedo suddenly went “beyond the control of the driver as it began to sway and jump in an alarming manner from left to right, and finally dashed off the roadway on the left, crashing into a number of spectators.”

“As the machine struck the crowd, it turned a somersault and then fell over. Everything was hidden in a cloud of dust.”

The devastating crash was described in other newspaper accounts claiming that Baker lost control when the wheels of the Torpedo caught in trolley tracks, while subsequent court records blamed the accident on the instability of the vehicle’s frame.

Whatever the cause, the race ended in tragedy. Two gentlemen were killed, and seven others suffered multiple life-threatening injuries. This marked the first time when spectators suffered fatal injuries during an accident in a motoring event

Fatalities withstanding, Baker’s achievement went on record that The Torpedo was clocked at 102 mph just before he lost control of the racing car. This was 34 mph faster than the existing land-speed record. In fact, The Advocate stated that just before he lost control, Baker sped past the three-quarter-mile mark in just over 34 seconds.

Both Walter Baker and his co-driver, E.C. Denzer survived the crash relatively unharmed, although it took some time to extricate them from the wreckage. According to court reports, the men had few injuries, listed as scratches on foreheads and scalps, caused when onlookers attempted to pry the wreckage away from them. Other reports state that Baker and Denzer were also burned from sulfuric acid that had spilled out of the broken batteries situated on all sides around them inside the car.

Interestingly enough, and another first for automotive history, their survival was attributed to the fact that they were both wearing seat belts, another early Baker design.

Just as he had hoped, Walter C. Baker’s recorded speed surpassed the coveted record that day, but the crash disqualified him from the race. In fact, both men were immediately arrested and put in jail for murder before charges were later dropped.

EVs: The Surge and Decline

Baker ended his racing endeavors not long after that fateful Memorial Day weekend, focusing instead on the commercial development of electric automobile production. Within a decade following the 1902 Staten Island race, The Baker Motor Vehicle Company sold tens of thousands of electric cars to the world’s wealthiest and most influential people. Baker’s electric cars were used in the fleet at The White House, and even the King of Siam ordered one with an opulent interior trimmed with ivory and gold.

The strongest catalyst in causing the obsolescence of battery-operated automobiles was Charles Kettering’s invention of the electric self-starter for gasoline powered engines.

Although Kettering’s patent was not issued until 1915, gasoline powered vehicle manufacturers started advertising new electric starters during the autumn of 1912, for their upcoming 1913 automobile production. Beautifully illustrated, large advertisements were deliberately positioned in the most prestigious newspapers and magazines, pointedly challenging the modernity and fashionable trends of electric cars.

One of Baker’s most aggressive competitors was Haynes Automobile Company from Kokomo, Indiana. Elwood Haynes targeted the fashionable, wealthy women who drove electrics in an open letter published in Vogue Magazine, September 1912.

Elwood Haynes statement as it appeared in “Vogue Magazine” for September 1912:

“The new electric starting and lighting equipment, now an integral part of every Haynes, removes the only obstacle that has kept a gasoline car from being A Woman’s Car. You could handle the new Model 22 Haynes just as well as any man. The starting crank is done away with. Getting out in the road to lights lamps is done away with. Start and light the car - every time - from the driver’s seat. It is a wonderfully complete automobile.”

Popularity increased when gasoline powered vehicles were designed to travel more efficiently over dirt roads in comparison to the electrics that worked best driving through paved city streets. Gasoline powered vehicles quickly achieved further traveling distances with much faster speeds. As Henry Ford developed his factory production capabilities, he manufactured 202,667 cars during 1914, all with a starting price that would please the general public, only $440.

By 1921, Ford offered a $20 electric starter as an additional option on all his vehicles. Electric cars were soon considered obsolete especially as gas-powered automobiles become entirely affordable to the general public. By the first quarter of the 1920s, Kettering’s Electric starter worked so well that it was installed in nearly every gasoline-powered automobile.

Today, most people never knew that electric battery operated cars existed 125 years ago. Even automobile collectors will admit that the old electric antiques are considered rare.

Yet, that time machine has started to whir again. In a world faced with such great environmental concerns, the development and renewed public interest in battery- operated cars does, in fact, appear to be the way of the future.

What a great article, so informative and interesting, I thoroughly enjoyed it, and I am so looking forward to future articles from Julia.

Thank you for the compliment! Please spread the news about Juicy History to your friends. Most of all, please know how much I appreciate your subscription. Sincerely!