The First “GPS” Device c. 1912: Jones Live Maps

The most incredible, early high-tech motoring gadget for wealthy American and European drivers.

Over a century ago, the hottest high-tech toy for your swanky automobile would have been, essentially, a “GPS” device.

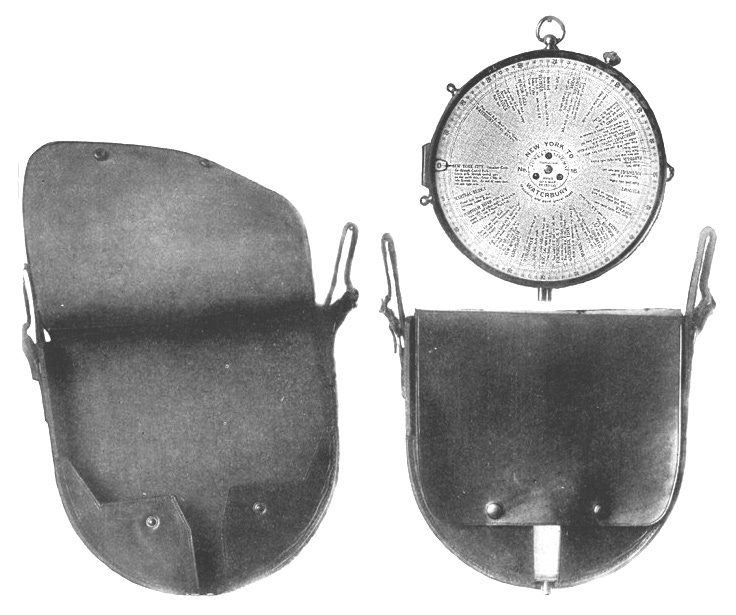

This was a beautifully designed set of automated directional maps with perfectly detailed driving directions printed onto celluloid discs. The discs were inserted inside a brass and glass domed apparatus that was attached to the wheel of the automobile with the dial mounted onto the dash or held in a passenger’s hands. The entire set was luxuriously cased inside a sturdy leather-bound pouch with a weighty brass closure. It was called the Jones Live Map and this was considered the most costly of all the accessories that a motorist could own.

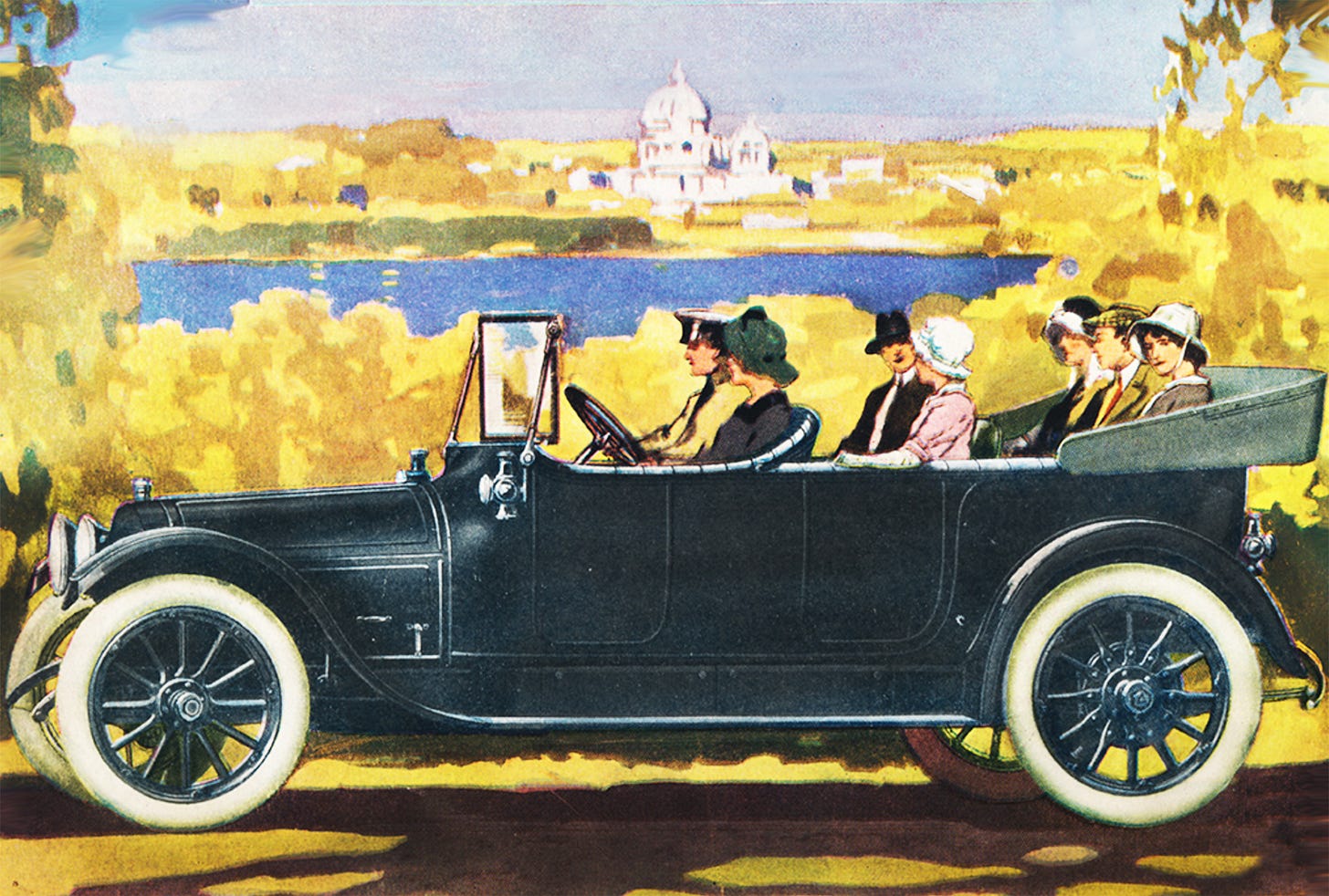

Early automobile driving was considered a sport for both men and women. and their luxurious cars were beautifully hand-crafted and often highly customized. Every nook and cranny glistened with opulence and elegance.

An onboard, real-time navigational system was just part of the lavish appurtenances designed for such exclusive cars. These high-tech toys were also prominently advertised in every newspaper, literary journal, and fashion magazine. Other rich automobile accessories from the Edwardian era included finely bound road atlases, ornate horns, sparkling brass speedometers and odometers, and even traveling ‘banquet boxes’ complete with portable refrigeration units.

By 1912, even the Special Autumn Millinery edition of Vogue Magazine reported on the latest motoring fashion trends for their stylish readers. An entire article was devoted to the lure of the Jones Live Map inVogue that September; an exclusive fashion magazine otherwise devoted to couture hats and evening headdresses.

“ While there is a certain amount of fascination in touring through unfamiliar parts of the country and in wondering what will be the view in store for us just around the corner, the driver must be forewarned of dangerous turns and steep hills, and must be ready to take this road or that at the next fork.

There are poor roads, of course, as well as good, and the average motorist ought to keep to the latter, even though the scenery on the better highways may not be picturesque.

The roads of this country are being improved at the rate of thousands of miles a year, and a route that may be almost impassable one season may be converted into a fine boulevard the next. For the tourist, road maps are issued every few months…and are indispensable.”

Vogue Magazine, Autumn, 1912

Certainly useful, the Jones Live Map directional device offered a real-time way to get from here to there without getting lost. Safety and comfort were especially important during an era when few roads were paved and when there were even fewer places to locate gasoline along the way. It was tricky to determine the shortest route to your destination and most drivers were well aware that their romantic motoring adventures could quickly become disastrous.

This early era of automobile driving was the time when most drivers depended upon finding directions and gasoline resources by utilizing help from strangers along the way. It was common to stop the car to knock on the door of a farmhouse or pull aside to call out to a random roadside bystander with the intent to learn if drivers were on the correct route, or not.

“Hello mister!

Yes, excuse me, please, but how do I get

to the Wilsons’ house in Amesbury?”

“Wilson who?”

Jones Live Map was destined to end this type of random interaction along the journey, especially when many well-intended locals did not give accurate directions resulting in a slew of complications, frustrations, and wasted time.

J.W. Jones invented the Live Map in 1909 and it was readily available to all well-to-do motorists by 1912. One version of the device was attached to a long flexible shaft that, according to the company, “allowed the instrument to be passed around inside the car to the passengers while held like a book.”

The device could also be hung in the tonneau or attached to the dash. But the most popular version of the Live Map was directly attached to the outer steering post of the car so that the driver could simply look over and read it.

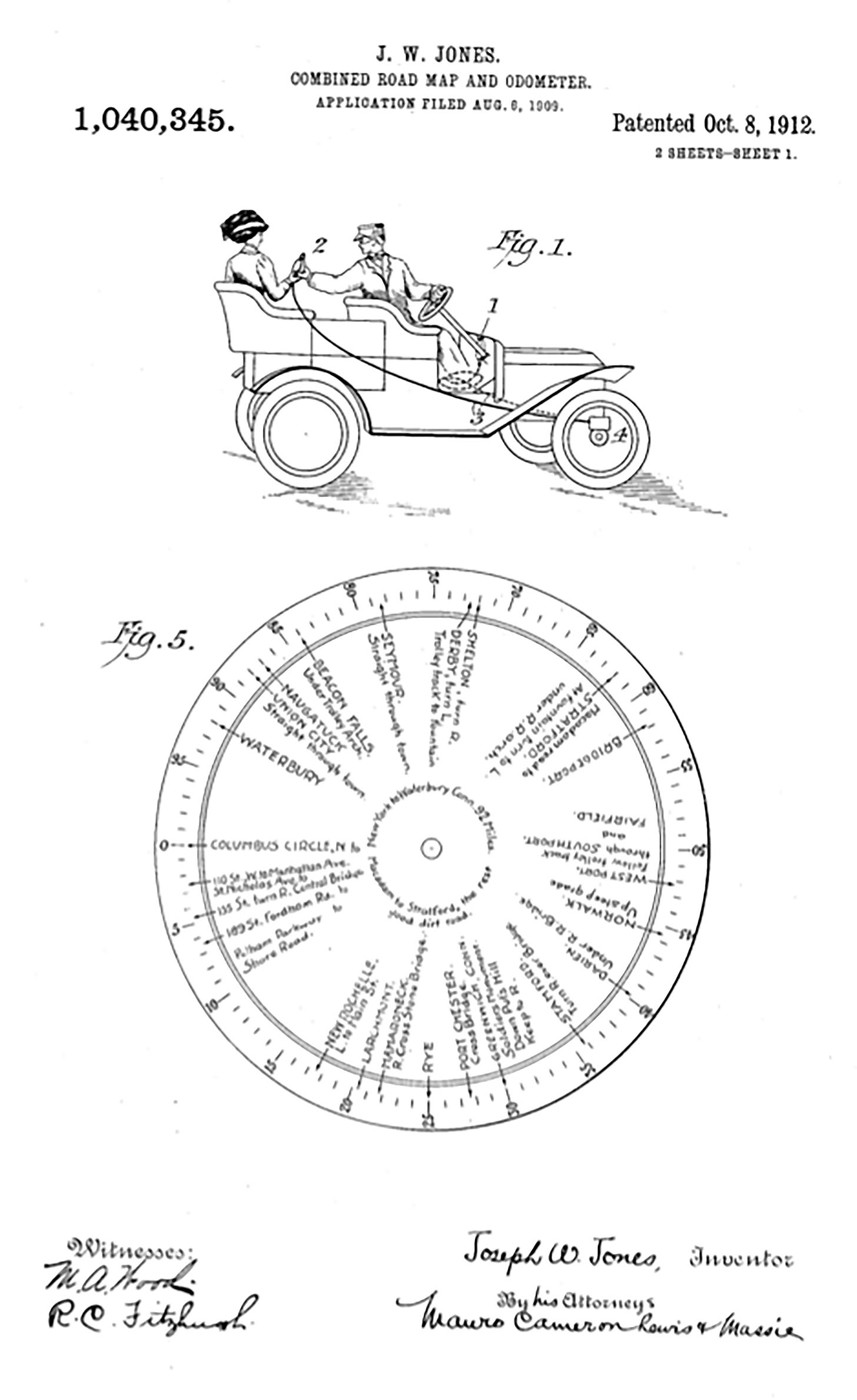

“The Live Map consists of a celluloid disc marked off on its outer edge with the various touring data included in that section. The distances between crossroads, turns, hills, or whatever other road marks are indicated and are placed in their proper relation to each other.

The disc, or map, is placed inside a brass receptacle and is connected

to the front wheel of the car in such a manner

that it will rotate at a proportionate speed.

A pointer on the brass receptacle indicates the position of the car as long as one adheres to the prescribed route. When the route is again taken up after a deviation has been made, the Live Map may be set so that the indicator will point to that locality at which the main highway is again followed.

Thus, it requires but a glance at the point to

determine the exact location of the car.”

Vogue Magazine, Autumn, 1912

The Live Map’s celluloid discs were marked with enough information to travel exactly 100 miles and were printed in heavy black fonts designed for easy reading in a variety of weather and lighting conditions.

All discs displayed the mile marker, as they slowly turned inside their glass domed case, while the automobile traveled along city streets or over remote rural roads.

City directions were easily followed:

“Cross the R.R. bridge,” the disc would read just after mile marker 71.

Then,

“Follow trolley.”

“Cross bridge and take left fork at Davenport Avenue.”

“Bear left one block on Broad Street.”

“Jog right and then left on College Street.”

Arrived, “New Haven,” Connecticut.

Whereas, in the country, detailed instructions read slightly differently:

At mile marker 81, “drive through woods.”

“Jog left, pass church, schoolhouse, and cemetery”

“Cross iron bridge, up steep hill, curving sharply to right.”

“Turn left. Winding road through.”

Arrive “Plattsburgh” Indiana.

The discs were made in a dial shape that was about 8-3/4 inches (about 22 cm) in diameter. Each disc was labeled with the names of towns, crossings, bridges, significant right and left turns as well as any other relative information that Jones thought necessary to navigate.

Discs would often also list the name of a specific hotel, restaurant, or other well-known area landmark found at a particular corner, fork, or junction in the road. Most importantly, the discs also reflected road conditions, known dangers such as rock slides or high water, and listed the types of road surfaces one was likely to pass over.

The Jones Live Map set included at least a dozen celluloid discs that would fit beneath the shiny glass dome. Once the odometer registered through one of the 100-mile sections, the driver would stop the vehicle and install the next disc in the series. This continued throughout the journey until the desired destination was reached.

Conceptually, the Live Map system was designed to immediately solve the struggles of reading Edwardian road maps accurately. This involved comparing paper diagrams to road maps, and then again to the odometer readings on the car.

As Jones advertisements reminded prospective customers during the autumn of 1911:

“You remember how bad it was at night when you blundered along, lighting matches, trying to see the figure on the odometer, then taking the wrong road in the dark, and then having to stop

at farmhouses to inquire about directions?”

“Do you remember how troublesome it was to keep your place in the map book, to check up mileage with the odometer on the dash - particularly when the wind was blowing and the rain falling on the leaves of the book?

Jones Live Map solves the touring problem.”

The company advertised that their high-tech Live Map tool was incredibly simple to use and highly accurate. They also compared the celluloid discs to the type of recording discs used within one of the first phonographs, the Columbia and Victor Talking Machines, which were considered another technological achievement during the early Edwardian years.

The Jones Live Map Meter Company was originally located in New York City and the invention was designed with the intent that it would eventually replace all paper maps throughout the world. Celluloid was far stronger than paper and far easier to keep clean and dry. It also had a decidedly rich appearance since the material was nearly identical to the look and feel of genuine ivory.

Celluloid, considered the first plastic, was quite familiar in the marketplace by the time Jones Live Map Meter was first introduced. It was initially developed in the mid-1850s, with the first material patent registered in England during 1867.

By 1870, American brothers John and Isaiah Hyatt acquired patents for their version of the plastic, which was a pressurized mixture of solid nitrocellulose, camphor, and alcohol. They officially registered this under the trade name “Celluloid” in 1873 and went on to manufacture piano keys, spectacles, and vanity wares. Celluloid was so prominent in the market by the 1880s, the trade name soon became a generic term which has carried through to this day.

The most exclusive version of the Jones Live Map was marketed inside a glamorous heavy-weight leather pouch trimmed with glimmering brass. This set came with 20 ivory-colored celluloid discs. Well-traveled and well-healed motorists were encouraged to build upon their disc collections. By 1910, an article in the January issue of “The Automobile” stated that Jones had created over 600 discs that accurately mapped out three major regions of the United States.

In the April issue of “Automobile Topics” that year, another article announced that Jones had updated his mapping system by “laying out a route from Tampa to New York, via the new capital highway.”

The time for expansion was ripe. In June of 1910, Jones and his wife became headline news when they set sail for England in their quest to make their business worldwide. There, the couple successfully spent over two months creating the latest version of his navigational instrument, documenting “routes all over the British Isles and Europe.”

By then, the Jones Live Map was considered one of the most luxurious of all automobile accessories. And, it was considered quite expensive with a starting price of $75. Additional mapping discs were offered at between 15 to 25 cents each during a time when the middle-class worker’s take-home salary was about $20 per week.

In addition to the Live Map, the Jones company also made luxury speedometers, odometers, clocks, and even a specialty horn called the Jones Yobel which was advertised as “the gentleman’s automobile horn that sounds with one harmonious and penetrating note.”

Certainly, the most costly Live Map model in their line was advertised within the Chas. E. Miller Supply House catalog during 1911. The 12-disc starter set in its chic leather pouch was offered for a high retail price of $130 making this the most exclusive of all the gadgets offered to wealthy automobile owners at the time.

By 1919, Jones offered over 500 sets of mapped routes from New York to Los Angeles with dozens of trips in between.

But with constantly changing data, the celluloid discs became obsolete and paper discs, which had been printed all along for Jones’ more frugal customers, became the norm.

Quickly, the tide turned for Jones when automobiles became mass-produced and an influx of drivers took to the highways. As routes were developed, corner schoolhouses and other landmarks were torn down, roads were diverted, and streets renamed. His mapping information became utterly impossible to keep up-to-date due to the ever-changing data that was required for each disc.

And so, the Jones Live Map Meter Company quietly ended production and closed during the early 1920s. Since then, no other automotive mapping system has been considered as successful, that is, until GPS systems became mainstream by the late 1990s.

Today, the Jones Live Maps are considered collectible and scarce. Christie's of London sold a European version of the Jones Live Map, without its discs or case, for a realized price of $143 US in 1996.

Then, ten years later, a 1912 version of Jones Live Map appeared at auction, offered by Skinner in Marlborough, Massachusetts. That set included the brass meter, 20 celluloid discs, and a well-used leather case.

On that day in 2006, this rare collectible sold for $764.

And with that auction comes the irony: Henry Ford listed his mass-produced Model-T automobile in his 1912 catalog for the very same price.

Recently saw this on an episode of "Mysteries at the Museum". Fascinating, right?

Fascinating!