In Their Words, Part 1: Covered Wagon Days 1895-1901

Historic Never-Before-Published True Stories From Newly Unearthed Pioneer Letters and Audio Interviews

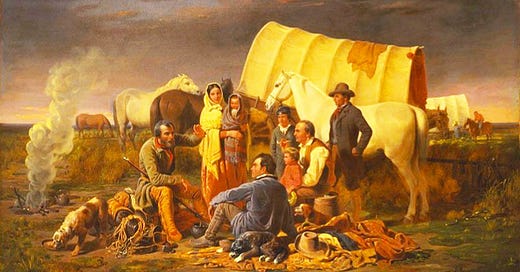

If there was any hesitation about traveling over 500 miles with four small children in an old covered wagon, using only a jerry-rigged 2x4 board for its brake, no one ever mentioned the thought.

This was simply the way of life in 1895, a time of make-do existence during an era of cultural extremes.

Like many other pioneers, this determined young family traveled in a well-used, but sturdy, horse-drawn covered wagon. They carried only a handful of treasured possessions that were packed tightly among camp supplies and baby diapers. As a family of six, they were armed with hope and faith as they drove toward their dream of building a more prosperous life. Daily chores had alone prepared them for the ruggedness of the trail, but their proclivity was to follow dreams over maps.

This family, like so many others, was drawn to the newly settled lands in Texas. They traveled with the knowledge that they could count on being supported, befriended, and defended by the close-knit church families who had already settled there during the early 1850s.

Long before the American Civil War, the Carr family had a well-established tradition of moving to new and remote areas in their heritage. They were constantly looking for that better deal: ideal farmland to build a plantation, a church, and schools.

Originally from England, their ancestors settled in Virginia during the mid-18th century. They soon moved south into North Carolina and then on to Georgia well before the turn of the 19th century. Eventually, the family invested in land near bustling Rome, Georgia, and established a thriving cotton plantation sometime during the late 1830s.

Decades later, as the American Civil War festered, James’ eldest sister Rachel and her husband, a Southern Baptist minister, made the decision to move away from Georgia with their siblings. By 1863, they had settled in the town of Rusk, Texas, where there were already established schools, churches, merchandise stores, a grocery, a jail, and saloons. Childless, Rachel and her husband cared for her youngest brother, James, but tragedy struck within weeks after their arrival to their new home. Rachel suddenly died.

Siddie, the second-eldest sister, quickly filled in for her sister with young James. Siddie married a young physician the following year, and James became further influenced and supported by a growing, well-educated family.

It is unclear as to what exactly happened. Documents were lost and family history became vague during the American Civil War.

Back in Georgia, the Civil War was raging. Their father, the family patriarch, passed away at the plantation. At the same time, their mother’s name disappears from records.

It is unclear what exactly happened, but it is well known that the war took a heavy toll on the town of Rome, Georgia. Stories within the family describe how their cotton plantation was burned to the ground by Union soldiers following orders from Major General William Tecumseh Sherman during his infamous March to the Sea. What is certain was that any chance of the siblings leaving Texas to return to their old home in Georgia ended abruptly, and forever.

Through the years, James grew close to his church family during the Reconstruction (1865-1877) but lacked regular schooling. Traditional formal education, once a prevalent option before the Civil War, was now limited to the most basic fundamentals in a rural one-room Texas schoolhouse.

Decades later, as a man, James was described as an avid reader and a soft-spoken gentleman. However, he often lamented that he had no opportunity for proper learning during the post-war years.

Eventually, in 1887, James married Julia when he was 28 years old. Julia was a younger, genteel Georgian woman who was well-educated and disciplined as a housewife.

Julia had grown up according to her father’s strong will. Their large and extended family had been, like so many others, displaced out of war-torn Georgia and they relocated to the wilds of Texas after her father was released from a Union prisoner-of-war camp. Julia’s mother, already an experienced pioneer woman, had eight children and was steadfast to her tough husband, always a military man, who became the first hard-handed sheriff of Camp Co.,Texas.

After their marriage, James and Julia dreamt of owning a plantation such as what they once knew, but James became a laborer instead. He blamed this on his level of education due to the war.

When their first baby, Ola, was born nine months later, James became adamant that none of his children would ever miss a day of school.

By then, political talk had erupted about free land opening up in Indian Territory, not far from the border with Texas. Free tracts of land would be awarded to the settlers who could stake their claim in person. The government’s offer made it apparent that to have the highest chance of success, one would have to live within a reasonable distance of the territory.

The Land Rush of 1889 was the first significant giveaway. President Benjamin Harrison proclaimed that a two-million-acre region would be open for settlement and a landrace was scheduled for April 22nd.

Harrison’s proclamation stated that settlers could claim 160 acres of land for free and then receive the title if they proceeded to live on it for a specific period of five years, build a home, and make other improvements. At the time, the United States was in the worst economic slump this country had ever experienced. People became desperate with hunger for that land, but the idea had mixed reviews throughout the rest of the United States.

"It is an astonishing thing, that men will fight harder for $500 worth of land than they will for $10,000 in money.”

The New York Herald, April 21, 1889: Oklahoma Historical Society

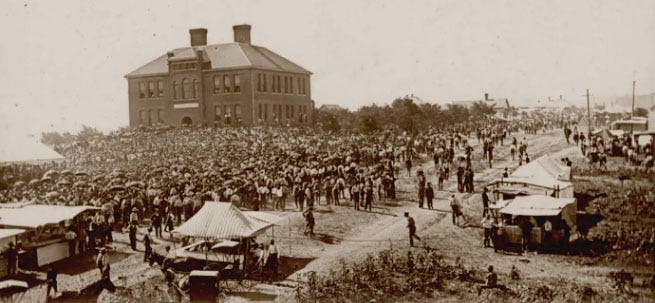

On the 22nd of April, nearly 60,000 people jammed into what appeared to be a wall of human life. They traveled on foot, horseback, and by every conceivable type of vehicle. People were tightly crowded together, lined up for miles. At straight-up twelve noon, cannon fire sounded and there was a wild cacophony of gunshots, shouts, and cheers signaling the rush forward. The contestants raced across the dry, hot plains in a thick fog of dust toward their dreams of acquiring free land.

“Yet, for many, it was all just for fun.”

An incredulous amount of people wildly raced one another with a deafening roar. Men and women from all walks of life barreled ahead and for miles with focused determination, plus a goodly amount of hysteria and chaos.

That day, there were only 42,000 parcels of land available. Later, it was estimated that there were between 50,000 to nearly 60,000 participants. Many who raced would not be successful.

Most contenders were on horseback or rode mules, some drove wagons or buggies, and there were those who walked; there were even reports of people riding bicycles. Eight land rush trains carried thousands of contestants. It was reported that the railcars were so filled with riders that they appeared swollen and ready to burst. Some desperate folks even crowded onto the roofs of the passenger cars, clinging for dear life, while their train rumbled through.

Then, after a settler thought he had successfully staked his claim, he had to do it all over again and race back to the Land Office where he was required to register the coordinates. Claims were not valid if this last step was omitted. Claims were disputed and widely contested.

Without a doubt, James and Julia discussed and obsessed over this risky venture of acquiring free land in Indian Territory. Instead, James took what he thought might be the safer alternative, and in the opposite direction. He was offered a job including a house on a cattle ranch outside Hondo, Texas, west of San Antonio. The couple liked the rancher who had made the offer, and James accepted the job.

With brazen determination, and their very young infant, the couple loaded a wagon and moved over 350 miles further south in Texas to their remote new home, located a few miles outside Hondo.

James worked as a ranch foreman running cattle for the following five years, but the young couple found life even more complex and unprofitable than they had imagined.

At the end of five years, they were a growing family living in a single-room, boxy wood-frame house with only a small smokey stove and a dirt-floor kitchen. They had little else. With the daily struggles and three small children by then, Julia became dearly homesick for her parents and siblings, who lived near Ebenezer, Texas, almost 500 miles away. She was heartfelt about leaving Hondo and dreamt of returning home again.

Finally, they agreed. James and Julia started to develop a plan to head north toward the Texas border in anticipation of another land rush. They hoped to live near enough to eventually and easily participate, but also within reasonable visiting distance from their families. By then, there had already been six land rushes, and the next was scheduled for May 1895.

Autumn came, and Julia discovered she was pregnant with their 4th child. She argued that she felt certain she could make the trip. The couple began to pack a covered wagon with the thought of moving the family as soon as possible before the birth.

But as their plan materialized Julia, soon grew heavy with pregnancy. It was quickly decided that covered wagon travel would not be safe.

So, as the seventh land rush commenced as planned on May 23, 1895, opening Kickapoo lands to white homesteaders, Julia remained at home in bed near Hondo, over 500 miles away. She had just given birth to their fourth daughter.

Undaunted, the couple continued to believe the news that more land would soon open again. As Julia nursed the tiny infant, the couple continued to pack for their move north. They decided to set out in a large covered wagon that would carry them for the nearly 500-mile long trek from Hondo to Montague, Texas. Their four young children, including the 6-month-old infant named Berta, would travel with them.

The young family scheduled their long trip for the month of December in 1895, knowing they would have to endure winter travel hardships to be near enough and timely for the next land opening. They felt sure that the next land rush would be scheduled sometime during early spring, or as soon as weather might allow. However, by this time, governmental scheduling information was often based on heresay and guesswork.

James readied their well-used wagon. It would be pulled by a team of horses and was covered with a freshly oiled canvas tarp to protect against harsh weather. They packed tightly, using every available inch of space for the most basic necessities, all while making room enough for their young children.

Ola, the eldest child, was 8 years old, and sister Iva was only 6. The two older girls were told to take charge of the tiny new baby Berta, as well as Bessie, the 2-year-old toddler. The children traveled inside the back of the wagon throughout the duration of their trip. James and Julia sat on a spring seat and drove from the front. In addition to the horses pulling the wagon, they also had a cow and a third horse tethered behind.

There were few roads and even fewer bridges over the many streams and rivers along the way. Whenever they had to cross a waterway, Julia took the reins while James would slowly, carefully, ride his faithful horse out into the water to check the depth with a long pole. If he decided it was safe, they would inch forward and ford the waters. If not, they would travel alongside the stream until they found a spot shallow enough to cross safely.

Ola later recounted her memories about this trip in 1895 in a letter that she wrote documenting the experience:

“We were leading on an extra horse, which Dad often mounted and rode out to test the depth, then he would return to drive us over the streams. This happened again and again and often with a steep bank to climb after, once we had crossed. It was all so very frightening at times.”

“And then, there we were, the six of us in an old wagon with no real brake.”

“Dad had used his do-it-yourself ability and devised a make-shift brake by nailing a 2x4 on the bottom of the wagon box and extending it out in front of the right rear wheel. He looped a chain around that wheel and caught it on the spokes so that it would lock the wheel when needed. Of course, he had to get out of the wagon every time to do this, and there were many steep hills along the way to navigate, which also often frightened us kids.”

“Our mileage each day wasn’t much, and the matter of a suitable camping place was an all-day-worry especially because of the cold, but we had to do it.”

Once James and Julia had decided on a good campsite, they prepared the fire and then fed and bedded the animals and family. They rarely stayed at the same camp for more than one night.

The nightly routine fell upon James and Julia alone to prepare the site since the children were too small to help. Ola and Iva kept little Bess and baby Berta distracted in the wagon, heavily wrapped in blankets, until the campfire warmed the night around them.

“Dad rustled the wood while Ma cooked.”

While they traveled throughout the day, James killed enough wild game for their nightly meals. They also ate from slabs of smoked bacon cooked over the open fire with dried beans and rice rationed from the food supplies they carried with them.

“Our cow gave small amounts of milk and butter but not much since she was walking so long and had to keep up with the horses,” Ola wrote.

There was a big mason jar filled with sourdough starter from which Julia would bake biscuits over the hot coals of the open fire. Even so, there were nights when food rations were meager.

The daily trek was intensely bumpy and uncomfortable. The travelers were constantly jostled to and fro; nodding off was nearly impossible. The air outside the wagon was cold and raw, but unpleasantly damp and stuffy inside. Baths were infrequent, and there were so many baby diapers that it created an odorous environment. Their four children always rode inside the wagon while tightly curled up inside thickly tented layers of quilts and blankets. The youngsters lived every day for a month between casks of food, tools and other supplies, while leaning up against trunks filled with family clothing, especially baby diapers (enough for two).

Ola wrote:

“Twenty-nine days all alike except for wash days!”

“One time, we set up camp next to the bend of a creek, and Ma informed Dad the diapers were all dirty.”

Therefore, the family decided to stay an extra two days to clean the wagon along with the usual chores and, above all, do laundry.

“So, the next morning, the washing was started. My job was to hang the clothes on the bushes and pick them up when they blew off. All day!”

“Then, around supper time, a nice woman from a nearby farmhouse came down in her wagon and brought us a freshly baked pie. She cheerfully told us, I thought your family might enjoy this for your Sunday night supper!”

All this time, the devout Southern Baptist family had been convinced it was Saturday, not Sunday.

Of course, they did not have a calendar. Their only easy reference to time was the watch that hung from James’ vest in addition to the changing sun as it rolled across the sky. Sunday was always the day dictated for rest, worship, and giving thanks according to their Bible. The realization that they had inadvertently worked during the Sabbath was deeply embarrassing.

“Then again, we did almost worse,” Ola wrote, “we lost track of the days a second time.”

“A week or two later, we drove until almost night and came to a country schoolhouse with plank floors and with no one around. So, we struck camp in the yard and slept in the building with a stove instead of on the cold ground near a dwindling campfire.”

“Early the next morning after breakfast, Ma commenced wash day so we all got busy and washed, then strung the wet diapers and clothing over the yard fence. We also covered the bushes with diapers and all else, including our underwear. Finally, we finished about noon.”

After their work was done, the family gathered around the fire and took lunch together while the laundry dried. Dozens of diapers and clothing hung from every available space; many garments would take hours to dry.

“Then, at about 2 pm, vehicles began to arrive! The people filed into the building for church! And that was the first we knew that it was actually Sunday! But, I can promise, we were quietly pleased that at least the washing was done!”

The family trek continued on. They drove their wagon and animals into a remote area near Nacona, Texas, only five miles from the Red River Valley. There, they were finally able to camp along the border with Indian Territory, just 8 miles north past Montague.

Along the way, James heard news of a seller willing to part with a small farm with an even smaller cabin. He sought it out, and paid $600. Unlike the house on the cattle ranch near Hondo, their new home featured solid floors and a large fireplace for cooking and heating. With meager supplies and few housekeeping possessions, James soon left Julia alone with their girls and found enough work as a farm hand and foreman at surrounding farms. He believed that his work as a laborer would bring in enough money to support the family in the short term.

As they settled in, according to Ola, the routine within the tiny cabin began well before dawn. James always tended to the animals whenever he was home and brought in enough daily firewood. Julia stoked the fire and cooked the family’s breakfast. Bess, the toddler, and tiny Berta were always dressed by their adoring father while Julia fed the older children.

One wintry morning, James pulled long layers of warm dresses over baby Berta and sat her in a big rocking chair near the fireplace before dressing Bess. Berta giggled and cooed with delight when she found she could rock the chair back and forth, when all of a sudden, the wee child tossed herself headlong out of the chair, onto the hearth, and into the hot coals.

James caught the screaming baby just after she landed. He grabbed her long fire-resistant woolen gown with a hard yank and pulled her out of the fireplace. Small glowing cinders stuck to the baby’s hairline, temple, and thumb. James quickly knocked them off with his hand, taking some skin.

Her father’s quick actions saved the child’s life. Outside of several minor burns, that eventually turned into lifelong scars, little Berta suffered no other injuries. Julia used a rosebud-based salve, one of the few “medicines” they carried with them, to heal the child’s blisters.

The anticipated land rush that they had so eagerly awaited did not happen. The family lived and worked for many years along the border of Oklahoma Territory, as the region was called by then, anxiously hoping for another opening while James continued traveling for work as a foreman at long-established regional farms. He often left Julia and the girls alone for weeks at a time. Nearly six years passed, and they were able to save money toward building the future homestead that they diligently prayed for.

Finally, in 1901, the government proclaimed a federal land lottery in the opening of Wichita-Caddo and Comanche, Kiowa and Apache lands. For all the obvious reasons, the chaotic, often dangerous, and commonly disputed land runs had been discontinued. Instead, there would be a lottery and settlers would register a chance to claim a 160-acre plot of land. The lottery was scheduled for July, 1901.

To participate, it was necessary to register in person at Land Offices in Lawton or El Reno. Ultimately, over 170,000 people registered; but there would only be 6,500 names chosen as land winners.

As an adult, and over time, Berta later recollected and documented the family’s experiences through written letters and extensive interviews based from her memories, in her own words, on audio recordings.

She reminisced:

“When the lottery was announced, Dad sold our farm and organized five other farmers and their families to go to El Reno by covered wagon train to register for the lottery.”

It was decided that once they got within a few miles of the lottery office, they would all legally camp on land owned by friends from their church. Yet again, James, Julia, and their four daughters would ride in a covered wagon carrying the newborn, a 7-week old baby and first son, Nolan.

It was agreed that James would lead the wagon train.

“At the beginning of the trip, there was only five miles to the Red River along the border. Of course, we knew that the river had to be forded because there were no bridges yet, but it was quite shallow, only about ankle deep.”

“Dad was the wagon master, and so he went first. He plunged in with the horses and got into the middle of the river, and that’s when the wagon started to go down. Quicksand.”

“Quicksand is very treacherous, and if you get into a deep bed, you’re likely not to get out. And so, the farmers all saw that the heavy wagon was going down fast because within minutes, it was down to the hubs. Everyone guessed there might be some kind of difficulty in crossing that river but they never thought there would be quicksand.”

“So the men on horseback trailed along the banks of the river, waiting for the best time to help. Calmly, Dad got out, put me on his back, and took me out of the river by wading around the quicksand. Then he went back in to get little Noely. He was just a newborn and Dad carried him out, put him on the bank, and told me to watch the baby. Next, he carried Bess out on his back. After that, Dad led the horses that carried the older girls and Mom to safety.”

“Then some of the men rode to the far side of the river and cut willow branches, ten to twelve feet long. Oh, they were vicious-looking things. They went back, and they lashed those poor horses, and they lashed them hard so that they would pull with all their strength.”

“The other men traveling with us pulled off their shoes and socks, rolled up their trousers, and waded in with shovels. They got down under wheels and pried the wagon loose as much as they could, with those two big horses pulling as hard as they could, and with all their might. It took two more teams from off the other wagons to finally pull our wagon out and then up over the bank.”

The wagon train, loaded with families, traveled for days toward El Reno, passing only regional Native Americans who rode silently past on horseback.

The Robinsons owned one of the covered wagons in the train, but they also drove a large herd of cattle alongside. They were were close friends with the Carrs and had daughters about the same age, along with three older boys.

“We youngsters rode in one wagon all day and played until we got cross with one another and ugly. Then, as the rules went, we had to get out, get in our own wagon, and take a nap. But those three older boys had to drive that big herd of Texas Long Horn cattle alongside the wagon train. It was all so slow moving back then, because cattle don’t move very fast.”

“We drove ahead, day after day. Then, every night, the families all worked together to make camp. That’s when they would bring out that big old cast iron pot and put it to heat over the fire.”

“Earlier, during the day, the Robinson boys would take turns shooting any game they saw as we drove along, and they’d strap it down to the front of their saddle. Then, at night, they’d skin it or pick it or whatever had to be done. The dinner recipe was simple, they threw all of it into that big pot!”

“Oh! My! What good eating that was. We also had big Dutch ovens that we’d put over the coals and bake them full of sourdough biscuits."

“For so many days, this was our ritual. We poor silly kids were too small to do any real work, so we’d get to run and chase each other and jump around the fire all evening. What a lark. It was lots of fun, lots and lots of fun,” Berta fondly remembered.

“In time, we got close to Chickasaw. We stopped to camp at Mr. Robinson’s brother-in-law’s farm. He was a widower but had two daughters who were the same age as my older sisters. He allowed us all to make use of his land as long as we needed before the land lottery.”

“During that first night in camp, I had a terrible earache, and oh, I cannot express how painful. One of the Robinson girls cut a piece from an old pillow case and sewed it up into a little pillow. She filled the pillow with salt and put it in their cast iron skillet over the campfire coals to warm. They certainly knew how to take care of things back then because I soon went into a peaceful sleep with that tucked against my ear. I’ve never had another earache since.”

More time passed. They all waited but eventually learned that the land lottery was still weeks away. Legally, no one could enter the territory involved with the lottery to camp beforehand, so James built a simple wood structure to shelter the family on the land their friend had lent to them. Not much more than big wooden box, James’ simple building had two rooms and a dirt floor that served as their family’s temporary home.

As time went by, the men grew impatient and concerned that the lottery land might not somehow be suitable. So, one night, James and his best friend, Mr. Robinson, decided to set out to look over the area they hoped to win in the upcoming lottery.

The following morning, the two men saddled their horses and were again gone for several days as they inspected the designated area. When they returned, James told his family that they were more than satisfied with what they had found.

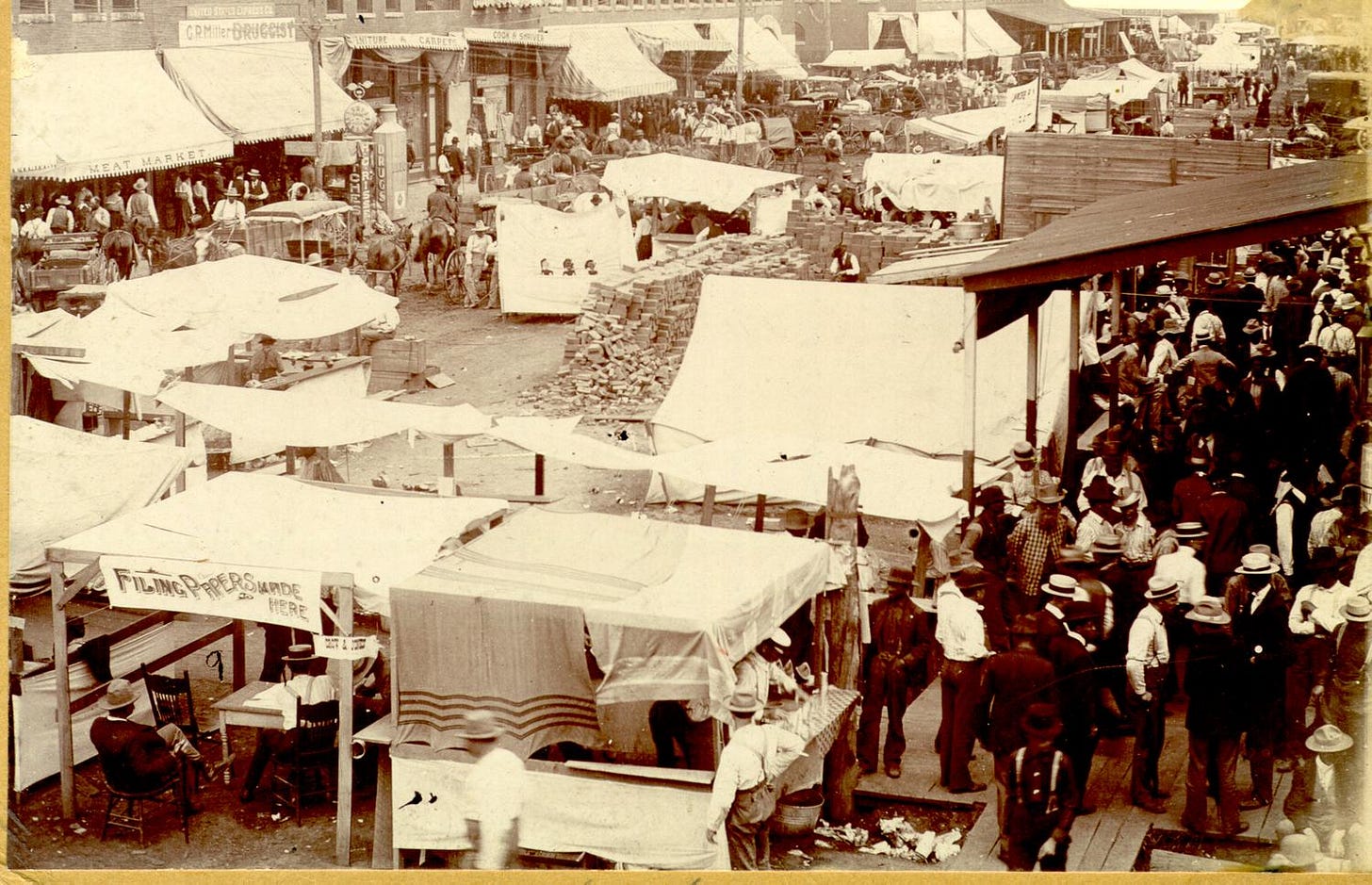

Finally, the lottery was scheduled and the farmers all left to register at El Reno.

“You had to go to either El Reno or Lawton, register, and draw a number. That number might be a blank or it might have a number and if so, you’d get 160 acres of land.”

Of course, Berta’s father described his experiences in El Reno during registration for the Land Lottery after he returned home. Berta recounted this in her letters and interviews.

“Thousands of people were there, from all over the United States. There were rows and rows and lines of them. Since this was a frontier town, they didn’t have near enough accommodations for so many people.”

“Dad got in line with thousands of others and then had to stand there by the hour, day and night, until the lines moved up.”

“There were no toilet facilities. No food. No water. Of course, there are always those men who follow such events. They just go for the heck of it, for the lark, and the experience to see what is happening.”

“And these men would get hold of some food and water and bring it to you for a certain amount of money. Or they’d hold your place in line while you’d go over to the bushes. When you got back, they’d give you your place back once you paid them.”

“This went on for days, or I don’t know how long, but I do know that Dad was gone for about four weeks.”

Julia and the children did not hear from James throughout this time, and missed him dearly. They were often desperate for news, and prayed together for his safe return. There was little time for much worry, however, because Julia and her daughters were busy taking care of young baby Nolan and the family’s daily basic survival needs. Yet, their challenges and levels of morale were helped along by the other farming families who had traveled with them in the wagon train. They had continued to live close by and supported one another.

Berta remembered:

“There were times, however, while Dad was gone when food was often not plentiful and then, our cow went dry.”

“We had cattle, yes,” Berta wrote, “but they were not really milk cattle, they were range cattle. Our cow was such an old cow by then; she had been giving us very little milk for a long time, and with food like it was back in the day, you didn’t have much to eat sometimes.”

“Then, a local rancher by the name of Mr. Bradshaw happened by on his horse. He said he was trying to get a mad bull under control and was heading out to the range. As he rode by, he slowed his horse and approached Mom. He said, ‘Mrs. Carr, I hear you don’t you have any milk or butter for these children?’

Julia replied, “No, that is so, Mr. Bradshaw, our cow went dry.”

“Well, Mrs. Carr, I have a young cow that just came in. Now, she’s wild, and you’ll have to break her. I will bring her over, and then you all can have butter and milk again.”

“And so, Mr. Bradshaw came back by the next day with that young cow. Mom and the two older girls went right to work as promised, and they broke that cow. They tied her hind legs and neck to posts so she couldn’t buck or bite. Then they milked her. After a while, eventually, she became gentle as could be and allowed us to milk her without any problem. Of course, after that, we had butter and milk again.”

Four weeks came and went while they kept house in their little one-room cabin.

“We loved Dad better than anybody,” Berta’s voice whispered lovingly. Then, with a long pause, she gathered herself during our interview. She seemed to be almost intent on listening in again to her father’s voice that echoed within her from so long ago.

“It was the day when Dad finally came home from the registering for the Land Lottery during the summer of 1901.”

“It was a hot summer afternoon, and while my sister and I were working outside the house, we looked up to see a wagon coming. It was a covered wagon but still so far away that you could only see the silhouette against the sky. There weren’t so many of those wagons like that in those days because there wasn’t much travel as it had been by then. But we recognized wagon and we knew the colt and we were sure it was Dad coming over the hill.”

“We didn’t tell anyone, we just tore out. Oh, we were running so hard, Bess and me. We ran and ran across the prairie because we could see him outlined against the sky at a great distance away. Oh, we just knew that was Dad.”

“And we ran so far that we were nearly breathless when we got there. Oh, and I’ll never forget how Dad easily got down off that middle high seat because it was a double bed wagon. He lifted both of us up carefully and said so softly, with smiling eyes, ‘now you girls mustn’t run so hard.’”

“And oh how we laughed and hugged him before we all climbed back into the wagon together and went on home. Of course, the others were all there at the cabin waiting for him too, my two older sisters, Mom, and the baby. It was such a joyful day.”

A few weeks later, James received what Berta described as a large, official-looking envelope. Her father gathered the family around, and opened it, knowing that the letter inside contained their fate.

Berta wrote:

“I remember how Dad’s hands trembled when he opened the letter. He read it quietly to himself and went silent. Finally, he said, “Mother, I drew a blank.”

“And so, that was the end of that dream.”

A few days passed. Dauntless, James and his best friend decided to travel again. This time, they rode together in one of the covered wagons on into the new territory, looking for desirable areas of land and those willing enough to sell their relinquishments.

“Many who registered were only trying their luck and not actually looking for a home.”

“Furthermore, my father wanted most of all to settle our family near one of the small towns that had sprung up overnight so that we might have access to a school, such as it was back then. He was anxious that his children have the opportunity for a formal education.”

Berta went on to describe that James later revealed to his family as to how he had to buy and sell several tracts of land before finally deciding upon the one he favored in particular, a tract of 160-acres in southeastern Caddo County near Apache, Oklahoma.

“Most importantly, Dad had been picky. This land was close enough to town so that all of us children could get to school each day by horse and buggy.”

Finally, James, with hired hands and friends, began construction on a new farmhouse that would be big enough to make a permanent home for his still growing family, after they welcomed a second son, baby Orville. They were now a family of eight, with six children and needed plenty of space.

When finished, their attractive Edwardian farmhouse was beautiful with multiple rooms, a modern wood cookstove, and a big front porch. The family would live out their lives on the homestead and even go on to raise a grandchild there.

Berta wrote, “On that beautiful spring day when we all moved in, it was rainy but sunlight grew strong enough to melt away those clouds. We were all dazzled as we drove the horses and wagons through the surrounding prairie lands, past the barn and outbuildings, then on up to our new home where we could see for miles in all directions.”

“It was such a sight, those rolling hills covered with lush, long, emerald-green grass and the countryside sparkling with raindrops in the sunlight. As far as one could see, this was all interspersed with big blue and white daisies.”

“We knew then that we had finally found our promised land, our forever home. The dream really did come true.”

Afterward:

Berta and Ola went on to live exceptionally long lives like many from their immediate family and ancestors.

At only 16 years in age, Berta started her lifelong career as a teacher. She first taught classes in a one-room prairie schoolhouse and then eventually attended University for her advanced degree in education.

Berta was proud to be a teacher and activist for the betterment of minority populations in the American West. She never married, saying that she outwardly rejected the thought of cooking and cleaning up after a man like a traditional housewife. Instead, she said, she wanted to live, what she termed, an exciting life, one that had meaning. Then, years later, Berta fell deeply in love with her good friend, a famous poet from her time. Sadly, this was unrequited love, it was said, because she was even more spirited than he.

At the end of her life, her niece sat next to Berta when she lay dying. As Berta drew her last breaths, her niece broke and started to sob.

Berta opened her eyes, and moved slowly to gently touch her niece’s hand.

She said, “Please don’t cry, Janey. It’s hard to believe the life I’ve known. Think of them all. I’ve met so many fascinating people over all these years. I’ve seen so many incredible changes in our world. Remember. I went into Indian Territory by covered wagon and then I flew in a jet plane to visit you when you had your baby. I have been blessed with a very long and special life.”

Berta and Ola were my Great-Aunts. I barely remember briefly meeting Ola who was quite aged and within days of death at the time. But younger Berta lived on. Her essays and editorials about the history of the American West were published in newspapers and academic books. She became my mentor in life.

Just before my teenage years, and over many days, I flew out to Tucson, Arizona where Berta was living at the time, and taped interviews. She willingly answered my often silly questions and told stories from her life and about others including people in our family, and of friends, acquaintances. She fully acknowledged that our world had rapidly changed during her lifetime due to technological innovations. She was a writer and historian by nature. Therefore, Berta wrote letters over the years documenting the now historic scenarios that she had experienced.

To touch on a few examples, while she was a young woman, Berta met Geronimo and other famous Native Americans. She studied the cultures, art, and languages of many tribes and often taught and grew respectfully close to her many Native American friends.

In contrast, Ola was involved in theatre. Her daughter, Florence, went on to be a model and actress who later married the famous actor Tony Randall. Whenever Berta was on vacation from her work as an educator, she often joined her sister Ola to spend time together in Los Angeles with Florence, and her friends, during the early days of Hollywood.

But some of the most interesting stories about the Carr family happened during the early 1900s at their Oklahoma homestead. Nearby neighbors were Frank James and his wife. Frank was brother to Jesse James and a member of the notorious James-Younger Gang of bank and train robbers.

Early on, Berta became fascinated by Frank. Her story about meeting him will be told here, in Part II, In Their Words, in Juicy History. I will publish this within about two weeks, so be sure to look for it!

Today, I own the original letters, documents, and audio tapes that tell Berta’s extensive stories from history. I am currently working on a complete biography of Berta’s day-to-day life, including her work with Native Americans. The articles I have published here in Juicy History are just the beginning of the many tales about this incredible woman.

Again, please be sure to look for my next email with Part II, In Their Words, via Substack that will be published sometime

within the next two weeks. As always, if you don’t see it, check your spam file or contact me directly. Thank you for reading!

Note: All text and images owned by me, unless otherwise noted, and copyright Julia Henri 2024, all rights reserved.

Fascinating! Can’t wait for Part 2!

So fascinating!! I can never find anything about covered wagon days, and so glad to read about your family. The many hardships and dangers they faced

makes one thankful for the sacrifices the families made to make our lives better.