Historic People: A Romantic Tragedy In Real Life, 1920s Movie Star Marilyn Miller, Part 2

The story behind the glamorous 1920s Ziegfeld Follies and film star who became namesake to Marilyn Monroe.

Findlay, Ohio: Autumn, 1920.

A true story.

Marilyn teetered back into the rocking chair on her mother’s front porch. Barefoot, she stretched out her legs and balanced both ankles along the edge of the porch railing. As she nestled down into the chair’s cushion, Marilyn drew a long pull on her cigarette through its ebony holder. She watched the smoke escape from her lips and scroll away, out into the warm Indian Summer air.

When a sharp breeze caught her long skirts and blew the expensive silk chiffon up over her knees, Marilyn didn’t notice. She simply rested her elbow on the wicker arm of the rocker, and held the end of the cigarette close to her face somehow fascinated with the twinkling orange smolder, as the flecks of tobacco burnt away and turned to ash.

The breeze kicked up again and blew the silk ruffles high over her legs, exposing a thigh; she flicked her cigarette onto the porch floor. Marilyn knew she appeared scandalous in small town Findlay, but improprieties were expected of her.

Little Emma May and her mother, Mrs. Gray, walked along the sidewalk past the Miller home. The child was dazzled by the sight of the petite, willowy woman in the wicker rocker with her brightly-colored silk dress floating in the breeze around her. To young Emma May, Marilyn seemed like a golden-haired apparition from a fairy tale.

“Please mama, can I go talk to her?” Emma tugged at her mother’s arm.

“No, Emma, not today. We mustn’t bother her.”

“But I want to! Why can’t I talk to her?”

Her mother paused to think of something to say; hoping to end the matter.

“Emma dear, we need to move along; she’s very tired.”

“But why is she so tired, Mama?”

Marilyn's sea-blue eyes rolled to one side and she looked directly at her neighbors, but said nothing. Although she knew them, and could hear them talking about her, she intentionally did not acknowledge them.

“She’s very tired Emma because," her mother paused, searching for an easy answer, “because she’s a dancer.”

Emma May Gray was one hundred and one years old nearly a decade ago when she recounted this story to me about how she met Marilyn Miller that day when she was but a small girl. And Emma May was perhaps the last person from Marilyn’s hometown who actually saw the famous actress who had been back to visit her family briefly, during a rehearsal break between Ziegfeld Follies appearances.

By then, Marilyn was only 22 and had already become a sensation in the theater, but her wholesome good looks and big smile were tarnished by a reputation that had started early on. Dancers and vaudeville acts were ripe with stories about that seedy side in life. She had started dancing and singing on stage, scandalously with her siblings under her strict stepfather’s supervision, when she was only 5 years old .

But what the neighbors in the Miller’s hometown may have never fully understood was that, by then, Marilyn Miller was also forever heart-broken.

Marilyn started dancing with the Ziegfeld Follies during 1918 when she was 20 years old, after spending most of her childhood touring in the family vaudeville act throughout the United States and England. When not on stage, the Miller family lived in small town Findlay, Ohio.

As her career progressed, Marilyn became a talented ballet and tap dancer, singer, model, and actress. She appeared in high-fashion magazines, on Broadway, and in three popular Hollywood movies before her untimely death at the age of 37.

Frank Carter, a vaudeville performer, became the love of Marilyn’s life. The two met during the summer of 1918 while World War I raged. As part of the Ziegfeld Follies, the opulent shows featured patriotic performances for wartime fund-raising including productions at the famous Casino Theater in New York City. The Ziegfeld program, like all Ziegfeld performances, was a lavish and costly production with numerous comedians and acrobats, exotic and grandiose costumes, spectacular sets, as well as fantastic music performed by the most famous composers and musicians. The shows featured unforgettable names such as W.C. Fields, Will Rogers, Irving Berlin, George Gershwin, and Earl Fuller’s Jazz Band. These stars performed the wartime fund-raisers alongside Eddie Cantor, Ann Pennington, Frank Carter, and of course, Marilynn Miller.

Carter had grown up in a circus family and was known for his acrobatic style of dance and crooning, romantic song. He was handsome and charming. The two soon fell in love and were seen slipping off time and time again between rehearsals for amorous rendezvous; often with the help of their close friend, Eddie Cantor, who was known as the usual culprit in secreting them away.

But Florenz Ziegfeld could not resist Marilyn and wanted her to himself. His amorous advances were little appreciated by Marilyn who had obviously fallen for Carter. Subsequently, when Marilyn and Frank announced on May 24, 1919 that they had eloped, Ziegfeld handed Carter his walking papers.

After that, and just as Ziegfeld intended, the couple were separated and apart for lengthy theatrical stints. Carter was forced to perform through different stage contracts in Chicago and Wheeling, West Virginia while Marilyn’s work continued with Ziegfeld in Philadelphia and New York.

Eight months after their wedding day, Marilyn went to visit her husband in Illinois at the end of his January performance run. For the first time, the couple’s schedules allowed them two weeks together and on one of those days, they attended the glamorous 1920 Chicago Auto Show.

It was quite the fashionable scene as the rich and famous admired the most luxurious and opulent of the new automotive designs. Of all the cars, the most spectacular motorcar in the Show was aptly touted as the 1920 Packard Special. It was a Twin-6, 4-Person Passenger Touring Car with a Fleetwood body.

Marilyn openly adored the automobile, which was considered the highlight of the Auto Show and described as one of the most expensive models in the world that year. But there was one detail that Marilyn was openly unimpressed with and that was the automobile’s gloomy color; an unusually dark and shadowy maroon.

Almost immediately during the Auto Show, it was announced that the Packard Special had been sold to an unnamed buyer. Also making headlines was the selling price of $10,000. Unbeknownst to Marilyn, the anonymous buyer was actually Frank Carter who had secretly purchased it as a surprise for their first wedding anniversary. And he quietly requested that Packard repaint the automobile’s color to a brighter, custom hue that Marilyn had mused would be more attractive; she called the color “fawn” according to newspaper reports. Frank also had their initials “F.C. and M.M.” embellished onto the doors; all for an additional $300.

Four months later, the motorcar was parked and waiting to be delivered outside the Packard offices in Detroit, Michigan. After Packard officials photographed the car for their records, it was delivered to Frank Carter in Wheeling, West Virginia where he was finishing up the last three weeks as lead in the musical “See-Saw.” But as soon as the press caught sight of the spectacular auto, once delivered, the secret was out. And Marilyn quickly learned through the media that the anonymous buyer was, in fact, her 28-year old husband who had purchased the Packard Special at the Chicago Auto Show. Yet, according to the press, Marilyn pretended she didn’t know.

When the last performance of “See-Saw” closed, Frank Carter set out to drive the Packard to Philadelphia where Marilyn was waiting. With him were three of his friends, actors and dancers from the show, and they left Wheeling just after midnight likely after a few celebratory rounds at the closing party.

The story moves quickly, as the local newspapers later reported. The men were driving the Packard Special through a mountainous region of Maryland just before dawn, at high speed. Carter was behind the wheel; the moon was full and the night, clear. He was anxious to get to Philadelphia, and there were still several more hours of hard driving ahead.

As he descended a long straight hill, the road ahead appeared to open up. Believing that he had finally left the mountains, Frank pushed on the accelerator. The car revved, gained speed, but just as a sharp hairpin turn appeared in the road.

The brakes weren’t quick enough to slow the vehicle, so Carter slammed on the emergency brake which threw the Packard into a hard skid. According to the reporter for The Republican that was published on May 13, 1920, “the momentum of the car caused it to catapult over the bank.” The magnificent Packard rolled twice before coming to rest at an angle on its two left wheels, nearly overturned, up against a high dirt embankment.

Two of the actors, Guy Robertson and C.J. Risdale, were in the passenger side of the auto. They managed to escape the wreck with only minor injuries. However, their two friends were trapped against the embankment inside the car on the driver’s side. Somehow, according to the reporter, the men managed to pry the top of the car up enough to rescue Charles Esdale, who had been sitting directly behind Frank. He was suffering from broken ribs and collar bone, as well as internal injuries. As for Frank Carter, his friends immediately recognized that he was beyond saving.

Since the survivors knew they were only one mile west of Grantsville, a village of only 260 residents in 1920, Robertson and Risdale started to walk the road hoping to find help. Not far from that fateful turn, they found a rural home belonging to Joseph Beachy.

With Beachy’s help, the three men struggled to carry Esdale away from the car and back to the house, when another car appeared on the road. It was the local doctor who happened to be coming home from a weekend visit with his mother, according to reports, and the doctor immediately attended to Esdale’s injuries.

Dr. Seán Henry is currently Library Webmaster and Historian at the Frostburg State University of Maryland. He stated:

“The road would have been exceptionally treacherous that night back in 1920. It was a mountainous section of U.S. Highway 40, which was a route that went all the way to the West Coast. That road was well traveled but known to be incredibly dangerous. In fact, several years before this accident, the government had gone into the area to photograph and survey that particular section of highway because it was in such poor condition. By 1920, that section of the roadway was decidedly considered one of the most dangerous highways in America.”

National media reported that Marilyn Miller was phoned in the middle of the night and told of Frank’s death. She handled the news stoically, they claimed. In the months that followed, it was said that Marilyn Miller was so strong that she took only a short time to mourn following her husband’s funeral. Her work offered peace and solace, the reports detailed.

But in fact, Florenz Ziegfeld had demanded that she immediately return to work, citing her newly signed contract as lead performer in the musical “Sally.” The show would open just 6 months later, only days before Christmas, and she was required to be there and rehearse as calendared.

Since that time, the press as well as biographers, have written numerous stories about how the young widow found escape through her work, especially so soon after the tragic event, and how well she recovered from the shock so quickly. Frank Carter’s life had simply slipped away, as they described it; he was gone quickly due to chest injuries and there was nothing more to be said.

When in fact, what happened to Frank Carter was far more devastating to Marilyn than anyone gave her credit for enduring. The truth to this story has never been told outside of the local Maryland newspaper until now.

The actual details came through the local reporter from The Republican who was on the scene that night. He wrote a most graphic and detailed account because he had rushed to the site of the accident after receiving a tip that Marilyn Miller’s husband had just crashed a car on Highway 40, nearby.

He apparently arrived soon after the crash, and reported:

“Frank Carter died instantaneously.”

“Carter’s head was caught between a boulder and the back of the seat, and the weight of the tonneau crushed his skull as if it had been an eggshell.”

He added that Carter’s wife had been “apprised of the accident by long distance telephone” but when she rushed by train to be by his side, Marilyn Miller did not know that her husband had died. She fully believed, in fact, that her husband was still alive and in a local hospital.

Another reporter for the Cumberland Evening Times was at the train station when Marilyn arrived and observed the entourage as they exited the passenger car. He wrote:

“Mrs. Carter arrived at the Queen City Station yesterday, with her sister who is also an actress. They were met at near the train by Mr. Risdale, who escaped injury.

Marilyn Miller, in great agitation, said, “Where is Frank? How bad is he hurt?”

Risdale replied solemnly, “Frank is not here.”

The young widow again said, “Well, where is he?”

Then Risdale said, “Why Mrs. Carter, Frank is dead” and the young woman collapsed into the arms of her sister as well as Mr. Risdale.”

The reporter went on to briefly describe how Marilyn was immediately required to go to the undertaking rooms in order to identify her husband’s body. She was also immediately obliged to make arrangements for his remains to be returned to New York for burial.

Biographers to this day claim that Carter died from chest injuries, but the Director of Reference Services at the Maryland State Archives, Michael McCormick, produced the official coroner’s report for this article and the declaration is succinct. Frank Carter died from a “fractured skull.”

The experience of seeing her husband’s face so badly disfigured, as legal accident identification required her to do, would have been the one experience that forever changed Marilyn Miller.

As years went on, Marilyn Miller’s difficult off-stage diva reputation grew right along with her fame and fortune. She was suffering in ways that few people realized nor understood.

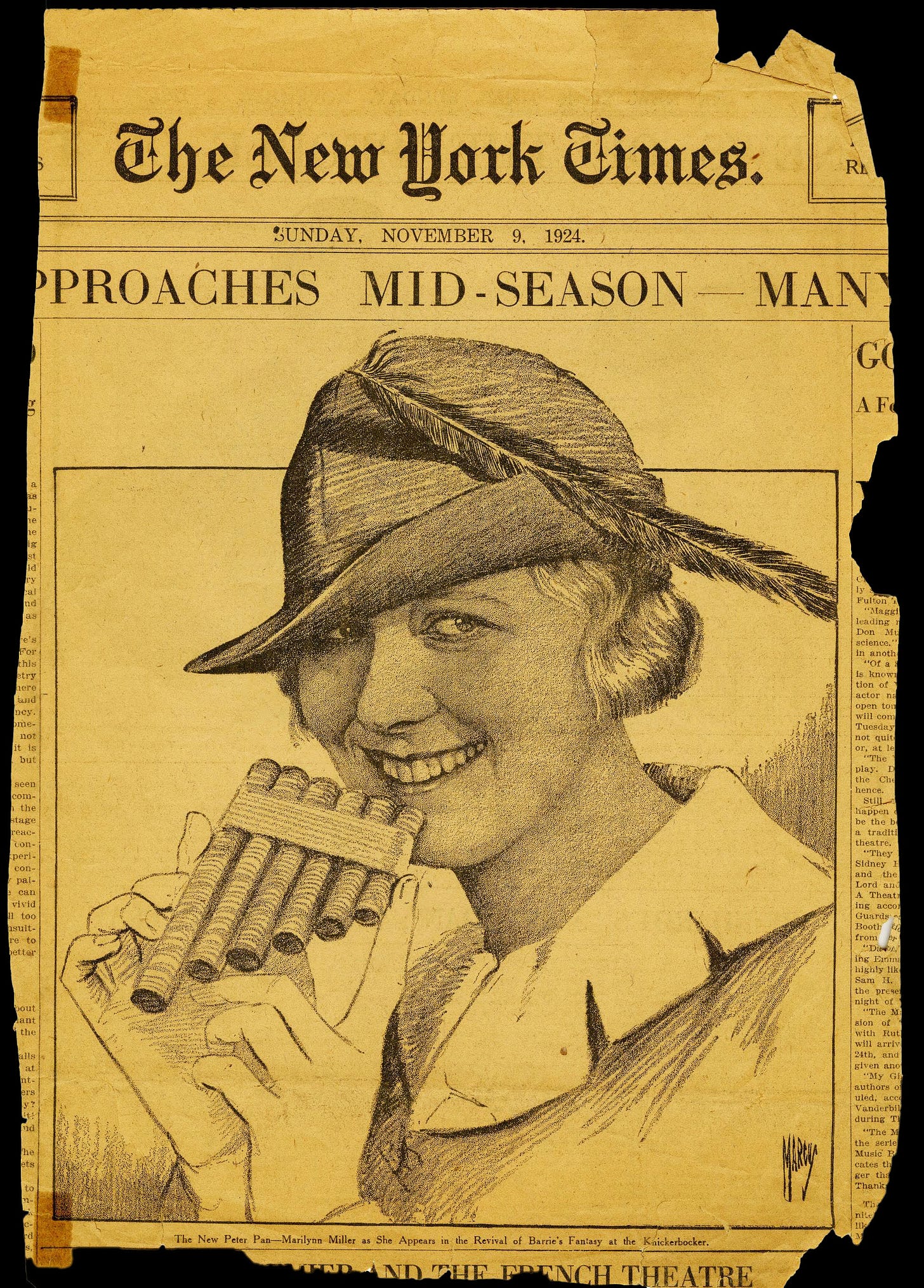

Then, in 1924, author James M. Barrie chose Marilyn Miller to play Peter Pan in the theatrical production. During rehearsals, there were several dance accidents especially during the special effects flights when she was suspended from high-tension wires. Marilyn was badly injured more than once but continued on with the rehearsals and performances without taking time to heal.

Later, Marilyn suffered from excruciating migraines due to her stage injuries that included a deviated septum which exacerbated previously existing sinus problems. There was no simple cure and for Marilyn, alcohol and pain-killers eased the pain.

However, gossip reporters from this time also tell of how the grieving young actress would leave the stage only to cry in her dressing room between numbers. Then, they wrote, she would return to perform in front of adoring crowds with seemingly unsurpassed happiness.

Not long before she started work on Peter Pan, and only two years following Frank Carter’s demise, Miller married actress Mary Pickford’s brother, Jack. More than one written account quoted Marilyn saying that her love for him was greatly due to his resemblance to late husband.

Eventually, Miller divorced Pickford after a difficult five years of marriage. She continued to work on stage and modeled couture designs for high-fashion magazines. She consistently worked through the migraines and medications, prescribed and not, which limited her abilities to perform. Her difficult personality became well known in the business but few understood just how profound her grief, due to the traumatic death of her first husband, had affected her.

Then she met Chet O’Brien, a chorus-line dancer who was 11 years younger than she, and they married quickly in 1934 just as the press declared Marilyn a fading star who had to buy love. The New York Times celebrity headlines read, “Musical Comedy Star [Becomes] Bride of Dancer Who Was In Chorus.”

By the time Marilyn was 37, the migraines and sinus condition forced her to seek surgery. Although the condition seemed to improve for a period of time after treatment, she relapsed. Again, in search of relief, she was ultimately given questionable treatments that, by many reports, amounted to medical quackery.

When Marilyn Miller died on April 7, 1936, one doctor stated that she had died from infection and swelling of the brain due to inadequate surgical procedures. Another doctor stated it was blood poisoning. Whereas her death certificate refers simply to a “high fever.”

After her death, the public and media mentioned the kindnesses that Marilyn Miller had quietly bestowed on others. There were many accounts where she donated money to help the poor and always requested anonymity. Her laugh was said to be infectious and her disciplined work ethic was far stronger than most ever gave her credit for especially after the shocks and tragedies that were so much a part of her backstage life.

She is buried next to her beloved Frank Carter at the Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx of New York. It has been stated that their marble mausoleum was paid for by the proceeds from the sale of the damaged 1920 Packard Special.

As for the car that was once considered one of the most exclusive automobiles in the world, it is considered lost. There is no record of an owner, nor even mention of its existence.

As one curator said, “no one has any idea as to what happened to the 1920 Packard Special. Of course, it would have had a seriously negative reputation since Carter had died in the automobile. But oh, what a treasure that would be, just to find it in an old barn someday [sigh].”

Too much triumph and tragedy for one short life. And Mary Pickford's sister-in-law, too!