Fashion History: Mannequins, Motors & Mechanisms...The Weird and Fascinating History Behind Early Retail Window Displays

Including the story about L. Frank Baum, who was a window dresser before he became the famous author of "The Wizard of Oz."

Even though many of us complain that the Holidays come along just a tad too early in retail stores for our general taste, marketing experts know that this is just the trick to manage the general public’s purchasing power. Halloween decorations share space with the first displays of Christmas lights, candies, and ornaments; all carefully positioned not long after our summer vacations have ended and sometimes even before the leaves change into Autumn colors. Regardless of how we may feel about it, retail store and window displays continue to catch our eyes every year, tempting us to buy just as they have for over a dozen decades.

The Victorian era marketplace emphasized window dressing more than ever before in a concentrated effort to entice paying customers. Sellers decked their small shops, booths, and carts with their most attractive, colorful baked goods, produce, dry goods and fripperies. They polished, waxed, and stacked apples and other fruits and candies so that they would glisten in the sun. There were tinkling bells, ribbons, and bright holly or pine boughs added to their Holiday displays. Businesses often featured an accordion or fiddle player prominently in front of their establishment for seasonable musical serenades.

Tantalizing window displays in the late 1800s became essential to shops and department stores; commercial decoration became a skilled trade. Creative craftspeople and fine artists were paid high salaries to develop elaborate exhibits of merchandise at the most exclusive retail establishments.

By the 1890s, window dressing became a highly respected profession. Commercial art schools offered classes on how to design windows, and numerous how-to books, manuals, and textbooks were printed.

One of the most popular of these early editions is now considered a rare, and valuable, antiquarian book; only a few original copies are known to exist. The book was written by author L. Frank Baum during the same time when he was working as a window display artist as well as editor of an advertising magazine called Show Window, that specialized in window display techniques. His profusely illustrated book, The Art of Decorating Dry Goods Windows and Interiors was published in 1900, only months before his renowned best-seller, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

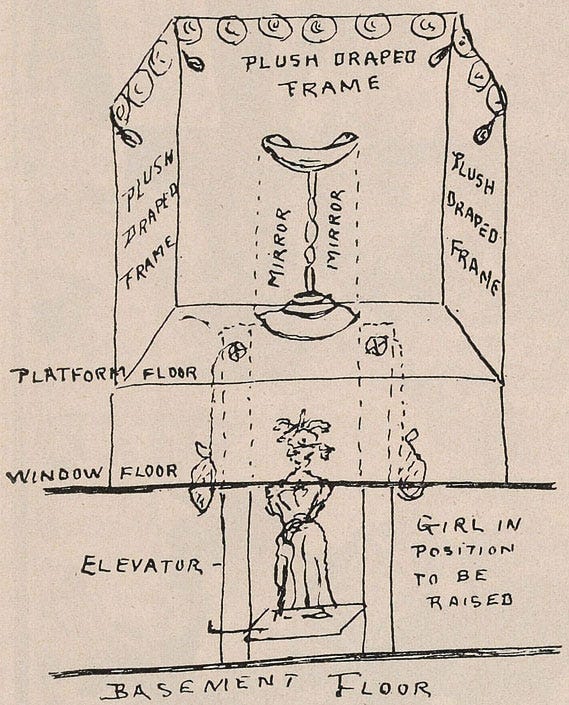

One of the most elaborate of all the window displays described by Baum was “The Vanishing Lady.” This was a mechanized attraction designed primarily for the display of fancy hats, fans, parasols and other accessories. Baum carefully described, photographed, and printed his hand-rendered diagrams inside the book detailing all the construction aspects of his illusion.

The moving centerpiece of the design featured a live model and is still considered a classic stage magic. The surrounding display walls were 7 feet tall and entirely covered with “plush” draperies and mirrors. Holes were cut into both the floor of the platform, as well as the window display flooring. A small elevator, strong enough to hold the female model (or mannequin) was constructed in the basement directly below. According to Baum, the elegant model would be raised and lowered in and out of the window display, therefore seemingly made to magically appear and then vanish, only to reappear again much like the magic trick as seen in George Méliès’ popular silent film from 1896, which likely inspired Baum’s window display (as seen below).

In Baum’s version, the fashion model was lowered into the basement, and a store assistant would help to redress her. Then, this Vanishing Lady would be sent back up to into the window wearing a complete change of costume.

“This attraction could be used to advantage for the display of millinery, fans, parasols, etc. The best effect is obtained by having the figure quite a distance above the spectator.”

“At short intervals, this young woman would disappear right into the pedestal (or so it would seem), and presently would reappear with new hat, waist, gloves, etc. This would continue, showing every ten minutes or so, with a complete change of hat, etc.”

From The Art of Decorating Dry Goods Windows and Interiors: A Complete Manual of Window Trimming, Designed as an Educator in All the Details of the Art, According to the Best Accepted Methods, and Treating Fully Every Important Subject by L. Frank Baum, Chicago, 1900. Reference: Yale University Library; Beinecke Library

During the Edwardian years, even the smallest shopkeepers went well out of their way to creatively decorate their shops and windows, especially during the Holidays. Bold papier maché Christmas figures featuring Santa Claus and angels, crêpe paper streamers, and pine boughs added that special touch to show off Holiday gift merchandise.

Behind the scenes, stores were well equipped with storage areas filled with wooden stands, mannequins, and other essential foundations for displays; all with backgrounds that resembled top-level theatrical sets.

The work was arduous and detailed. If a shop or department store owner could afford to do so, they purchased their backgrounds and foundations ready-made. Store and window display supply houses and manufacturers were common in Germany as well as France by 1905 and eventually made their way to England and the U.S within the following decade.

For every window change, trimmers and dressers, as the window designers were called, had to upholster every inch of those rough but sturdy stands and foundations with fine laces or luxurious fabrics to make them appear attractive before they were used to display merchandise.

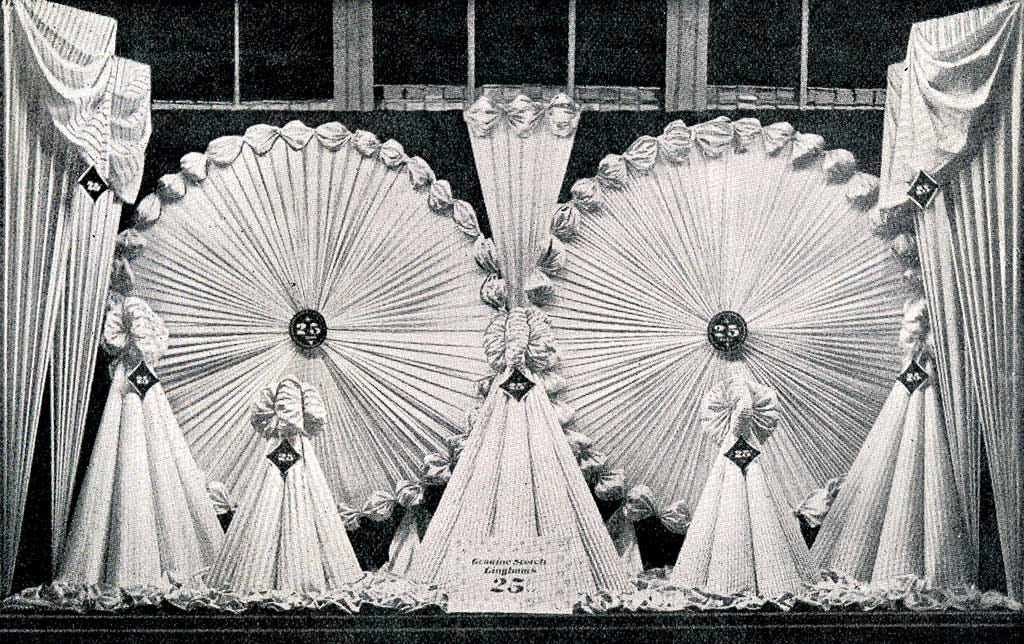

Massive, elaborate bows, puffs and free-standing geometric fabric sculptures, with paper cone supports hidden inside, were designed by master craftsmen who also taught eager apprentices how to copy their work. Eventually, drapery designs had common names and were universally referred to as Bag Puffs, Fan Puffs, Flounce Drapes, Puffs with Pins, Fluted Folds and more. Elaborate and labor intensive, these colorful fabric backgrounds enhanced both merchandise and mannequin displays.

Winter scenes in store windows were often the ultimate challenge, especially when it came to creating snow and ice.

“There are several good ways of imitating snow and icicles. One way is to paint a display heavily with white Alabastrine and, while still wet, blow in mica crystals, commonly known as glitter or flitters. First-class icicles may be made on strings first dipped in glue which raw rolls of cotton are stuck on making in various icicle shapes. Then dip these into a solution of gelatin the consistency of ordinary syrup. When dry, they make fine icicles that will not melt in any temperature. A layer of ordinary wheat flour, on which mica crystals are scattered, produces an extremely realistic imitation of snow; but raw cotton or cotton batting is generally used for snow effects.”

From the International Library of Technology: Dress Goods, White Goods, Clothing Published by the International Textbook Company, London 1903 and Scranton, PA 1905. Personal library collection owned by Julia Henri.

Clothing mannequins, busts, as well as millinery and jewelry heads were life-size and produced as men, women, and children of various ages. The earliest heads were made from bisque, but later they were wax or wax-over-plaster with thick human hair elaborately coifed into the most fashionable hair styles. The hair was often not styled in wig form, but the head was laboriously fitted with individual hairs that were actually handset into the wax scalp, strand by strand. Brows and eyelashes were also made from human hair; the delicate curled lashes fluttered over medical-grade blown glass eyes. These full-size mannequins had heavy, posable, wooden bodies with articulated joints much like those used in their smaller toy doll and marionette counterparts.

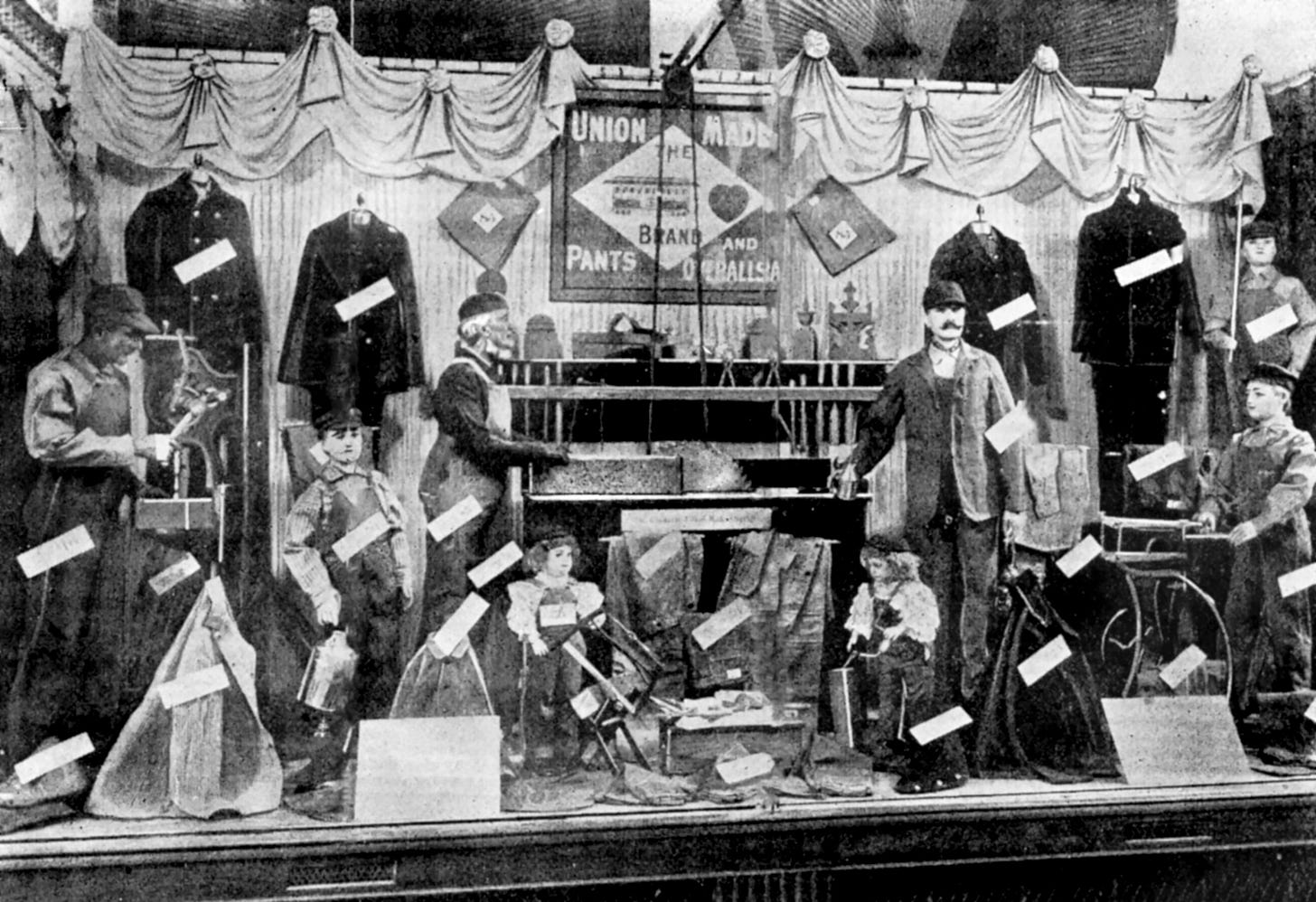

Trimmers were not only called upon to build interesting and fanciful window designs featuring the most costly merchandise for elite clientele, but they were also hired to create eye-catching displays that would appeal to the working class.

In one textbook, it was recommended that a rotating circular saw should be chosen as the featured eye-catching centerpiece in a working men’s store window. One can only imagine the dangers associated with such a tool endlessly spinning away inside a store display; the fumes from the gas motor that kept it running throughout the day (and much of the night) were likewise ominous.

“A very fetching window display of workingmen’s clothing and overalls should [surround the circular saw]. This is one of those painstaking efforts that the public always accepts as being very clever. The circular saw is regularly geared up and kept running by connection with a small motor, thus making a mechanical centerpiece [to the overall design]. The posing of the workmen and children [mannequins] in overalls is extremely good and worthy of special attention.”

From the International Library of Technology: Dress Goods, White Goods, Clothing Published by the International Textbook Company, London 1903 and Scranton, PA 1905. From the personal library collection, owned by Julia Henri.

The most elaborate window displays attracted the public like spectacular circus sideshows year around, but were especially popular during the Holidays when large crowds would gather to view the latest in specialty gifts and elegant fashions exhibited behind glistening glass.

During the late Victorian era, it was popular to feature automatons in all window stagings regardless of the season or occasion. But by 1905, these automated dummies were considered gauche and quite out-of-fashion by the most exclusive department store owners who openly refused to display mechanical animals or human-like characters with moving heads, arms and legs.

However, such mechanized and robotic creatures were deemed otherwise acceptable for use in professional children’s window design, although typically only during the Holiday seasons. This style preference has remained relatively unchanged for well over a century.

Instead, the rule of window design during the Edwardian and Post-Edwardian years favored first-class theatrical sets. Skilled carpenters built entire rooms called “Interior Displays” for the most exclusive big-city department stores. These fanciful set designs were popular with spectators and were showcased behind massive windows that typically lined the entire storefront in the most luxurious upscale buildings by this time.

Every interior room design was different for each window and featured ornate moldings, elegant fireplaces and faux marble columns; all made of light-weight wood that was covered with a plaster solution, and then painted to look real. Background scenes were rendered by hand in oil on canvas by the most talented fine artists, and installed exactly like those used for pricy classical theatre productions. Furnishings, carpets, and elaborate accessories were specially commissioned for many of these sumptuous Edwardian stagings, and glamorous mannequin families were posed as if sharing afternoon tea or an elegant evening affair together.

Such elaborate and ostentatious windows always drew large crowds. Newspaper reports from this time relate that the police were often called to handle the pedestrian traffic when the most ornate window displays were unveiled. Hefty iron bars were installed in front of the windows so that the throngs of people would not lunge forward and break the plate glass that separated them from the displays.

There are also numerous stories that describe department store windows as a general public nuisance due to so many gawkers. Some complaints claimed that too many people, especially those from every social class, were crowding together along the sidewalks and into the streets. Such window displays especially allowed the middle and lower classes to innocently peek into the fabricated homes of the most wealthy Edwardian families; the select world of materialism that was typically off-limits to all but the upper class was openly on view.

During the turn of the 20th-century, New Year’s celebrations were seemingly endless and lasted for a few years both before and after New Year’s Day 1900. Many magazine and newspaper articles, as well as advertising, promoted every imaginable preparation for all those additional holiday dances, parties, and dinners.

In one trade textbook, window designers in 1905 were still talking about turn-of-the-century celebrations and how to design the most chic contemporary window:

“For a New Year’s Display, the theme is the ushering in of a new century, which is cleverly idealized by bursts of light and the heralds with trumpets in the background. A grand stairway and colonnades on either side make elegant settings for the display of the selections of the reigning fashions of dress at this the century’s opening.”

From the International Library of Technology: Dress Goods, White Goods, Clothing Published by the International Textbook Company, London 1903 and Scranton, PA 1905, private library collection, owned by Julia Henri.

Eventually, laws and restrictions regulated window designs. For stores selling fashionable clothing of any kind, ordinances were passed that required shops and department stores to cover their windows with cloth, or paper, during costume changes; the mannequins’ nudity was considered obscene. Mannequin busts, by law, had to be removed from the countertops whenever an article sold and it was required that they were redressed in the privacy of a backroom. On Sundays, all window displays were typically shrouded with curtains or paper that completely covered the windows.

Customers soon caught on and responded dramatically to the visual messages in the windows and free-standing retail displays. If a window was filled with too many random colors and decorations, or crammed with too many goods, consumers interpreted the store as one with low-quality merchandise. If a window displayed only a few items that were beautifully lit and styled in front of a richly pleated backdrop, the very same customers were more eager to buy regardless of the actual quality in the merchandise. They also expected, and accepted, that prices would be higher.

Today, the same successful selling strategies continue to be used in retail window and floor displays. The mannequins and their surroundings are artsy, high-tech and bold. Visual advertising and merchandising concepts are carefully analyzed, scrutinized and applied to every market. But behind it all, those old tried and true window displays from the Victorian and Edwardian eras form the foundations for what we expect to see every time we shop at stores today, whether Saks or Walmart; we remain enchanted.

Enjoyed the elaborate displays! The Vanishing Lady was very interesting.

I thought this was another fascinating article by Julia Henri. So interesting how the displays would attract so many different people from different classes.