My one genuine need and joy in life is writing a good story about the people, places, and everyday life events from our history. I love to conjure all those phantoms from the past, gathered together in my imagination, whenever I hear their names or read their stories from my beloved library of antiquarian books, magazines, and random ephemera. Through old documents, imagery, and interviews with experts and museum curators, I try to track down and discern the truth in their stories and seek out lost details of lives lived before us. The resulting articles hopefully offer anecdotes and narratives that are relevant and matter in our often far more complicated world today.

When I feel that intrinsic tug at the beginning of what I think might be a really good story, the feeling is almost like a haunting…yes, almost. And when that feeling strikes, I can’t let go. I want to know more. I want to find the truth. This passion made me create this Substack newsletter, Juicy History.

It is not easy for me to be vulnerable….

However, writing about myself is much more challenging. This is no doubt surprising to some who are closest to me because, to them, I tell all. But I’m typically quite reserved about my innermost feelings, especially in public.

Many other Substack writers excel at crafting essays that read like personal diaries, creating a sense of intimacy that makes readers feel part of an ongoing conversation with close friends. Their words fly off their fingers with personal details, opinions, and profound observations about daily occurrences in every genre. I do not seem to fit into that category as a writer—at least, not when the story is about my personal life, as it is.

It is not easy for me to be vulnerable, but in our society today, social media has made it a necessity, if not an absolute requirement. This trend of voyeurism is stronger than ever, and publishers repeatedly remind professional writers to indulge their readers in descriptions of their lifestyles and intimate moments at home to better connect audiences to their published work.

While I was gone these past months,

I promise I’ve not been lazy, indifferent, or forgotten any of you.

Until now, I haven’t truly explained my long absence from Juicy History, but friends and professional associates have urged me to do so. Your ongoing subscriptions, at all levels, have meant so much to me throughout this time, and I am sincerely grateful. Since I last wrote, my subscription count has increased weekly, which has been the most potent encouragement. You gave me a great pat on the back, and most of you didn’t even know it.

So now, at this point in My Story, I want to make this quite clear: Juicy History might have seemed silent these past many months, but I have not been lazy, indifferent, or forgotten my responsibilities to any of you.

As I said, to my great delight and surprise, I have seen the Juicy History subscriber count grow instead of decline during this time. Some of you even signed up for paid subscriptions and became patrons. Out of the hundreds of subscribers, I only have one who moved on. Such positive overall statistics have filled me with creative joy and hope.

Please know that I am heartfelt. Thank you for your faith and for keeping your subscriptions active. I truly appreciate your incredible loyalty.

Considering this, I will finally explain why Juicy History has been silent for so many months. I owe this explanation to each of you.

As some may remember from an earlier update, I wrote about a "medical emergency" that prevented me from writing as intended. At that time, I chose to skip the details, thinking this was the most professional approach.

Back then, I honestly believed I would be able to continue writing intermittently as I began to recover, wholeheartedly believing I’d quickly move on without further health complications. I thought no one would miss me much, so I decided to try to quietly return to work and sidestep the drama.

But then, I soon realized that simply sitting upright for any time had become a real issue. Thinking, creating, and writing cohesively did not happen again quickly, if at all.

The medical emergency was, in truth, an unexpected diagnosis of a relatively rare form of breast cancer. That said, I should add that many people don't realize that there are various types of breast cancer, each with different stages and incremental details, all requiring often vastly different treatments. While all forms of breast cancer are dangerous and difficult to endure, some types are more seriously aggressive and life-threatening than others.

As I had no hereditary occurrences of any cancer on either my maternal or paternal sides historically, my mother, grandmother, and I all share a history of fibroadenomas. Thankfully, for each of us over the decades, the subsequent diagnoses, tests, and surgeries were always relatively easy, swift, and reassuring: benign tumors, nothing to worry about.

Until now.

By the time I scheduled that fateful mammogram, I was long overdue. I had discovered a new tumor growing in the exact spot where I had a large fibroadenoma surgically removed back when I was in my early 20s at the Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Again, that first tumor had been deemed harmless at the time—no big deal. So, I brushed off that new lump, thinking it was just another benign issue. Yes, this second tumor was one I would have to deal with, but…later. To further complicate matters, I excused postponing a mammogram, frankly, even longer due to my fears of contracting COVID-19, which was raging across the world at the time.

But then, something different happened. Over only about a week or two, I realized that the lump was growing, and quite rapidly. This realization was significant, so I called my esteemed GP at the University of Virginia, and she reacted with urgency. Within days, I walked into the UVA Breast Care Center for the mammogram, knowing that they would probably recommend tests and surgery just like the last time. I was calm and resigned; after all, I had done it all before and determined that I wouldn’t take anything too seriously. I planned to methodically go through the processes ahead and then return to my life, just like before.

However, my mammogram appointment became noticeably slower than usual. At one point, and interesting to note, the technician showed me the images, indicating that the new tumor was located precisely where the previous benign fibroadenoma had been. One could even see the scar tissue from the decades-old surgery in Boston.

Then, I was asked to wait while the doctors discussed the results. Within minutes, I was told an immediate ultrasound was required. I shrugged. Again, no surprise. This was all just like it had been done in the past.

As I sat in the waiting room, loosely dressed in a hospital gown, I realized I would soon be late for a luncheon appointment with a new friend. I texted her to apologize. She was already biding her time at the outdoor café. She texted back with a photograph of a glass of wine in front of the empty chair across from her.

“If you don’t get here soon,” she wrote, “I will have to drink this myself.”

Just then, I was interrupted and ushered into the ultrasound room. I put away my phone, still chuckling at her amusing text when I sat down in the examining chair, and as expected, the ultrasound progressed much as I had remembered from the past. Feeling confident that this was all basic hospital procedures, I was amiable and relaxed with the doctor and her two medical students in attendance.

But the room became unusually silent, and I glanced up into the eyes of the sonographer. I observed that she was extraordinarily fixated on her screen. Her eyes were steady and focused. She was frowning. I stretched my neck further to see the screen, hoping I could somehow understand the imagery. No. The darkness of the monitor filled with random, slowly moving lines and shapes meant nothing to me.

Typically, patients are not openly diagnosed on the spot. The tests are commonly studied, with subsequent treatment outlined, before the patient is advised during a one-on-one consultation within a day or two later. But that afternoon, the breast cancer had obviously and significantly grown so that both the mammogram and ultrasound immediately confirmed the most apparent and worst possible diagnosis.

“You need to call your family and gather everyone around you,” the young doctor said solemnly but with great kindness. “This is very serious.”

With fear, I immediately realized the severity of it all. But, no, I argued. This isn’t possible, I said, as I tried to remain professional and control the emotions cracking through my voice. I thought, I have always been the healthy one who was tough to keep up with in daily life, so no, this wasn’t possible.

I replied firmly that I would like further tests. She responded flatly that she was proud of her expertise and never wrong. I glanced at the two students who had been watching this unfold. They were both staring at the floor with a controlled absence of expression.

Tears slowly escaped down my cheeks while I tried to steady my composure. A loud inner voice sharply protested this diagnosis, but I said nothing more.

Truth be told, I knew I had dense breasts because my mammogram results over the years had been at issue more than once following that initial surgery in Boston. After that, I had even been misdiagnosed as possibly having breast cancer twice through smaller local hospitals during a time when I was moving around this country. Both times, I immediately sought out second opinions from prominent doctors at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and then a second time at Ohio State University. Both times, the university hospitals intervened with a whole new battery of scans and tests with their more advanced mammogram equipment and academic medical experts proving, yes, thankfully, I had been misdiagnosed and that, yes, thankfully, I was just fine. Nothing to worry about, they said; you just have dense breasts, and although tricky to diagnose, there are no tumors.

Similar breast tumor issues had happened to my mother and grandmother back in the day. They were also told that they had dense breasts. They, too, had fibroadenomas and went through scans, biopsies, and surgeries. But in the end, no one in our family had ever been ill with any type of cancer. No, there simply wasn’t any cancer in my family whatsoever, and most relatives had lived to be quite aged indeed.

Again, I repeated, this had to be wrong. I even asked the medical director if my medical records could have been somehow mixed up. But my protests at the UVA Breast Care Center were intelligently and gently countered with my every suggestion and protest. Biopsies and treatment consultations were immediately scheduled.

After the mammogram and so much discussion, I was among the last to leave the Breast Care Center that day. The empty lobby echoed, and the parking lot seemed unusually vacant as I went, amplifying my sense of being alone. But I was focused on hoping the newly scheduled biopsy would soon prove it all wrong. Yet, I also somehow knew that this time was different. There was a knowing, an experienced sense of urgency, I had noticed, with the medical staff as they readied to try to save another life, just as they do every day for thousands of other women and men who pass through their doors.

I drove the scenic road over the beautiful Blue Ridge Mountains toward home while I cried. I knew I would have to be very strong. Somehow. Whatever might happen next, this would be one tough ride, and I would have to do much of it alone.

The diagnosis: HER2+.

Statistics indicate that only about 1 in 5 people with breast cancer will be diagnosed with this type. This is not hereditary, I was told, more likely environmental. The exact cause remains unknown. Treatments for HER2+ are considerably different from the treatments for other forms of breast cancer. There is only one other type of cancer that is typically more challenging because there are far fewer successful medical treatments available. Thankfully, I had options.

Shannen Doherty, the late actress, was one of the notable individuals who battled HER2+ breast cancer. Like me and so many others out there, I read that she had postponed her mammogram testing, even though she had battled cancer once before, primarily due to fears related to COVID-19.

This past July, Shannen Doherty passed away after learning that the breast cancer had spread to her brain and bones.

In comparison, thankfully, and unlike Ms. Doherty, my saving grace is that there has been no indication of metastasis following numerous tests and biopsies.

I was also informed more than once that if I had been diagnosed with this type of cancer roughly ten years ago, my chances of survival would have been significantly lower. Shannen Doherty was first diagnosed in 2015.

Back at the café that day, my friend drank my glass of wine and then went on with her day without me. But my life had just forever changed. I tried to pull myself together but felt my body and mind rapidly draining of my goals, career schedules, hopes, and dreams. I thought of the exciting high-profile clients I was scheduled to meet within the following weeks and how every contract would have to be canceled, as the doctors indicated would be necessary. Life’s priorities had radically shifted to simple survival and endurance.

HER2+ breast cancer. The UVA hospital physicians and staff surrounded me with tremendous focus on making me a cancer survivor. They were incredibly kind and generous in how they supported me through the following many months of intensive chemotherapy sessions, each typically lasting about eight hours.

At my first chemotherapy session, I was sedated and groggy, but I remember asking when my hair would fall out. I tried to be dignified and collected, but the knowledge of going bald filled me with absolute dread.

My oncologist kindly told me it typically took two or three chemo sessions before hair loss happened. She offered a prescription for a cold cap, often used as an attempt to stop alopecia during chemotherapy treatments. But she added that with the medications used for my type of cancer, there was little to no hope that a cold cap would work at all. Also, scalp cooling therapy costs hundreds of dollars per session, typically is not paid for by health insurance, and would make each chemo session last perhaps hours longer in time. For me, she advised against it.

The following week, I felt relatively fine after that first treatment. Then, a day or two later, following my usual morning shower, I flipped my wet head upside down to blow dry my beloved shoulder-length mane up from underneath. When I flipped myself upright again, I stood naked and in shock at my reflection in the oversized bathroom mirror.

My damp body had long hair clinging to it, but also, long hair covered everything in my bathroom. The cabinets, the shower curtains, the shower rod, the toilet, the floor, walls, towels, and even the ceiling had hair dangling. Wisps of hair floated in the steamy air like long, slim confetti. All of a sudden, I had become nearly bald after unknowingly blowing my hair all over my wet self and the surrounding room.

I was too overwhelmed to think, let alone cry. My stomach knotted up, and I struggled to understand what to do with the mess.

My immediate thought was to call and beg for an emergency appointment at any local hair salon. But then I imagined the elegant salon ladies gawking at me. No, I would skip that idea. I couldn’t bear it.

After further consideration, I concluded there was only one thing left to do, and I promised myself that I couldn’t make anything worse.

I did exactly what so many other women have done—just what we see in all those dramatic movie plots about women facing cancer.

I dug through my cat’s supply drawer and found a relatively new set of cat fur trimmers purchased a year earlier. I shrugged. These shears had worked well on her, so I guessed they’d work on me too.

It was amazingly quick to do and I was soon shorn down to gleaming baldness. However, cleaning up all the hair that covered the room took a couple of hours and when finished, a big ball of dark brown locks filled a tall white kitchen trash bag. Finally, there was just one more chore left to do. With shaking hands, I went to my desk, turned on the computer, and ordered a black cap from Amazon, the kind typically worn by bald cancer patients. Rush delivery.

And that was the day when I realized I truly had breast cancer.

As the next few weeks passed, every hair on my body, including eyelashes and eyebrows, disappeared. Throughout the rest of that first year and a half, my body underwent even more physical changes due to the intensities of medications and high levels of chemotherapy. Symptoms were often extreme and incredibly embarrassing. Sometimes, I had to throw away my clothes because of it.

I was frequently amazed that any body could even do what mine did.

Like so many other women and men with breast cancer, I underwent countless surgical scans and tests. Throughout my long journey, I experienced a few memorably painful procedures, surgical procedures, urgent blood transfusions, and multiple doctor-ordered trips to the ER for more tests, fluids, and critically needed medications, all while being closely monitored each day by hospital and Breast Care Center physicians and staff. I remember being pushed in a wheelchair through medical building hallways because I couldn’t walk more than a few feet at a time. I learned to talk to myself quietly and calmly saying I needed to push one foot in front of the other just to make it out to the car for yet another drive to the Breast Care Center.

“You can do it,” I said to myself, “just get that foot in front of the other. There you go. That’s it. Keep going."

Ultimately, I went through the mastectomy and opted for reconstruction at the same time. The mastectomy and reconstruction surgery would be painful and harsh, I was told, but I would heal within a few months. And then, and best of all, the worst of it would be over; I would be on that final road to full recovery.

Or, so they thought.

About two weeks before the big surgery, a preparatory surgery was required. Somehow, while I was being intubated, a front tooth cracked. Two nights later, it broke off at the gum.

The hospital reacted immediately and sent me to one of their dentists. She advised that the tooth would need to remain as it was until after I had healed from the mastectomy. This was because it was too risky to undergo the long mastectomy/reconstruction surgery while wearing a temporary crown, as the tooth might fall out and cause choking.

I was resigned but did not suffer the indignity of walking around in public with a noticeably missing front tooth for the following three months. Thanks to my compromised immune system, my mouth was always covered with a COVID mask. For the most part, no one saw, and no one knew.

That mastectomy and reconstruction surgery took over four hours, with a team of three surgeons working together. There were significant incisions on both breasts. An impressive 17” incision went across my stomach, hip to hip. This was where tissue was taken for use in rebuilding my right breast, whereas the left breast had been reshaped to match.

Following that long surgery, I woke up looking up at a young resident who had been assigned to check on me. He eyed me closely to see if I was conscious.

I smiled back.

He cringed.

Struggling in the daze of anesthesia, I tried to understand why he had flinched. It took a moment, but I finally imagined what he was seeing.

Me.

My face and head were perfectly hairless. I had bloodshot eyes with dark circles staring out from within an otherwise pale and bloated face. I was skinny and sickly, with a big black hole in my mouth where my front tooth had been.

I struggled to speak intelligently through the meds, but the impatient resident spoke over me. Without a pause, he smoothly went through the usual routine and explained I would be recovering in intensive care and officially mentioned that the surgery had gone okay, for the most part. I remember thinking, “did you just say, for the most part?”

He talked to me in a slow voice, using language as if reading from a children’s book. I almost heard him say A is for apple, B is for breast, M is for mastectomy. I floated along with the drugs but wondered why he was talking to me like that. Then, it seemed he had judged my education and intelligence based on my grim appearance.

As he turned to leave, I called out from my bed:

“Excuse me, please, Doctor. If you have a minute.”

He turned immediately at my voice and moved back to my bedside.

I mustered every ounce of energy to speak clearly, rationally.

“I do have questions, please. But first, I need for you to understand. While I don’t have any hair or a front tooth, I do have an education. Please, I would appreciate if you would speak to me accordingly. Thank you.”

He seemed quietly unsure. No answer.

“Okay?” I said encouragingly, “let’s try again.”

With that, he engaged in a dialogue that was refreshingly respectful and intelligent until I nodded off. Although the caring hospital staff was superb throughout my stay, this scenario happened more than once. I found myself often explaining to medical personnel that I was not the ignorant caricature that I appeared in my grim, toothless appearance.

When the chief surgeon arrived later that evening, he informed me that, during the mastectomy and reconstructive surgery, active cancer was found. That was not usual, he said, and unfortunate. Therefore, the upcoming treatment plan required new protocols.

Changes. Again. I slowly took in that the potent and horrible HER2+ chemo cocktail I had endured for the previous six months-plus had, in fact, not destroyed that cancer as it should have, as it typically did.

My surgeon is a man I greatly respect, and he was sincerely disappointed with this news. He explained that my treatment would have to continue with a second lengthy series of strong chemotherapy again, following many weeks of daily high doses of radiation to ensure the cancer was entirely erased. It would risk my life to do anything less.

HER2+ is known for aggressive and swift reoccurrence.

Fast forward. Today, and at this point in My Story, I’ve finally gone through the worst. I feel positive, hopeful, and confident in my progress. I’m healing and working hard to recover from this long battle.

I will always be deeply grateful to everyone involved with my (still) ongoing program through the UVA Breast Care Center. I have sincerely thanked my surgeon and oncologist more than once, right out loud, for saving my life.

Grateful.

When I rang that chemotherapy bell for the second time, a large group of medical staff members stood around me, clapping. Throughout treatment, primarily during the scariest moments, I learned they would always be there to help. They never failed me. I never felt alone as I had initially imagined.

After that big brass bell finished ringing, I thanked everyone. I told the group that I had counted and had interacted with well over 150 medical people directly involved with my care at UVA. Out of those 150-plus individuals, I said with a chuckle, only three were on “My List.”

That statistic represents the extraordinary odds involving the high level of professionalism at UVA. In other words, out of the well over 150 medical professionals who were responsible for my treatment, only three didn’t make the cut in my personal book.

Thankfully, my doctors, all prominent physicians, tell me I am healing and right on schedule. In fact, I ask them repeatedly if I’m lagging behind in any way. I even asked yet again yesterday. Healing takes time, they always reply cautiously, sometimes an extraordinarily long time.

The fact is that my long-term prognosis is highly favorable. I am assured that the HER2+ cancer did not metastasize to my lymph nodes. According to most statistics, I have a 99.3% chance of survival in a five-year period. After seven years, I will be categorized as “cancer-free,” and the endocrine treatment I am now required to take, will end.

Out of those seven years, this makes year one.

Symptoms from chemotherapy and radiation treatments, as well as medications, can take anywhere from a few short months to as long as several years to subside entirely.

The Mantra: “Everyone is different.”

Although many patients recover relatively quickly, just as many do not easily return to living life as they once did. Breast cancer recovery is not like getting over a bout of the flu or even a broken arm.

The ongoing question is always:

“When will this all end?”

The answer is the never-ending UVA Breast Care Center mantra:

“Everyone is different.”

For those recovering from high levels of chemotherapy and radiation treatments, healing can become an exceptionally laborious process, again, often quite lengthy. Healing can take far longer for some than for others.

For me, the treatments and reconstruction part of the mastectomy went quite well. But daily high doses of radiation after the surgeries changed things. As months passed following radiation, my body responded with a vengeance and produced abnormal, sometimes painful and unusual amounts of scar tissue throughout the mastectomy areas and beyond. Due to this, I have been advised to undergo another three or four corrective surgeries during the coming year, that will add at least another chapter to my journey.

Patience.

Patience eventually becomes a fine art for most cancer patients.

In addition to that long list of physical changes that take place during the battle, day-to-day life often changes dramatically.

Family interactions change.

Careers end.

Financials are exigent.

Those extreme and often embarrassing physical side effects typically linger on for a significant time following high-level doses of chemotherapy and radiation. I haven’t described those side effects here, and for good reason.

Eventually, and for nearly all patients, side effects eventually do go away, but high levels of chemo-related symptoms can last (for some patients) far longer than two or three years following the actual treatments. Sometimes, I am told, longer.

Therefore, I’ve also found that some of the most challenging changes with breast cancer involve friendships.

Early on, the nursing staff at the UVA Breast Care Center wisely warned me that it is not unusual for friends and even family members to disappear abruptly following such a diagnosis. This is, I was told, a common occurrence for cancer patients. And, the nurses advised, when that happens - and it will happen, they said knowingly - just let them go. Ghosting is not anyone’s problem but their own in this situation.

Within My Story, I have only known three people who seemingly evaporated. In fact, due to this, I have returned to the same nurses to report that they were correct, and thanked them for telling me ahead of time.

One of the most challenging changes in living with breast cancer involves relationships with loved ones.

But oh! What exceptional, extraordinary kindnesses I’ve had from most of my friends and even the most brief acquaintances throughout this time!

Yet, like all cancer patients, I’ve also heard far too many hurtful and insensitive statements.

Here’s just a few:

“Kate Middleton didn’t lose her hair, so why did you? She looks great, and she just finished chemo. Did you hear she’s even gone back to work already!”

“My friend never took this long to get over breast cancer.”

“I had breast cancer exactly like yours twenty years ago. You should be over that by now.”

“All this has certainly become your very own reality by now, hasn’t it?”

“How long could chemo symptoms possibly take to go away? Haven’t you ever talked to your doctor about sleeping all the time? Are you sure you’re not just depressed? Maybe you should get some anti-depressants so that you’ll feel better.”

“Why are you so worried about your hair after all this time? Everyone knows chemo treatments make even more beautiful, thicker hair. Haven’t you ever heard of chemo curls? Everyone gets those eventually. You just really need to be more patient and stop worrying so much. Hey! Or why not follow the fashion trend if you're that preoccupied? Just shave your head! Haven’t you ever thought of doing that?”

And, finally, the one comment that sometimes lingers like some kind of curse,

“You sure have a dark cloud over your life, don’t you?”

But, of all, the leading ignorant and inappropriate statement was:

“You know, I hate to say this, but don’t you ever just want to just go ahead and die? Get it over with? I mean, all this hospital business can’t be fun.”

Umm. No.

Judgements. People say the damnedest things, as the cliché goes, and this is the short list of comments that made me lie awake for at least one night.

Inappropriate judgments. I have since decided to restrict visitation rights with people who make remarks such as these because the stress attached isn’t worth my very precious time.

However, the bottom-line retort is, again, that mantra:

When it comes to breast cancer recovery time, everyone is different.

Recently, there was an upbeat episode of My Story, and this was when my GP, a renowned medical ethics professor, enthusiastically suggested I consider writing a memoir about what I’ve experienced as a breast cancer patient.

I discussed the idea with another respected friend, a retired hospital psychologist who has her own profound and very personal story about experiencing debilitating breast cancer treatments, followed by a long time of healing.

Then, I also discussed these ideas with my UVA Breast Care Center social worker, whom I speak to weekly about my progress and whom I admire and appreciate more than I can say.

Both women agreed with my physician.

They urged me on.

The concept of my memoir would be based on the hope that sharing my personal experiences might help others in some way. Indeed, I have learned so much along this cancer-filled timeline, especially how to investigate the seemingly endless avenues of foundations, societies, institutions, and advocacies available to patients, friends, family, and caregivers.

Some of these non-profits are renowned for their professionalism. Others are legitimate but little known; most are inundated with help requests, and few can respond to more than a handful of individual inquiries. And, yes, there are those groups that are sketchy and worth the effort to avoid.

After learning how to search for and navigate resources, I’ve found help in paying my bills and support through valuable and reliable information, especially when I felt overwhelmed with worry.

Through it all, I have also learned the skill of patience, especially as a solo woman who has had to speak up and advocate for myself by myself.

The staff at the Breast Care Center sometimes called me their “long hauler.” This was because my treatment time was much longer than usual.

Today, I am slowly learning how to rebuild my life, day by day, and sometimes hour by hour. Most of all, through it all, I’ve kept my heart positive and avoided depression.

Cancer-related funding and support options, as do treatment sciences and technologies, change almost daily in our fast-paced world. Many organizations I relied on have already closed or significantly changed their programs. Other groups are trying to gain speed while battling the seemingly endless problems associated with inconsistent funding and donations, in addition to lack of volunteer support; all due to the rising economic burdens in this world.

Meanwhile, due to the restrictive costs involved, most financial resources are only offered to cancer patients who are actively taking chemotherapy and radiation treatments.

Throughout my diagnostic and treatment time, I did not keep a journal. This was intentional because I planned to move on quickly and without looking back. There was never any thought of writing publicly about my personal life. That is, until my physician and others urged me to do so.

However, with long production timelines, I’ve come to believe that a book would be obsolete by the time it takes to write and market it.

Yet, I do not want to discount the great intentions and opinions of the three women I admire greatly. So, what can I do now to help others?

If there is any breast cancer patient or caregiver out there who would like to ask about any of the resources that I found helpful along the way, please don’t hesitate to send a direct message through Juicy History. Maybe I can point you to avenues you didn’t know about. These might include finding assistance for medical bills, transportation, and day-to-day expenses, including emergency pet care. .

I will try to answer promptly, individually, and ethically to all who write.

If my lessons can help to ease yours, I’m all in.

And so, now is the time to look ahead!

Lessons.

The biggest lesson I have learned about myself is that I am unhappy unless I conduct research or write about a project.

The proof to that is that I often catch myself smiling while I sit and write for hours each day. Again. Finally.

And, I’ve promised myself to aim for happiness as my number one goal during whatever time I have ahead on earth.

Therefore, several new articles will be published soon in Juicy History!

The first of those, after this, will be published directly following this one. You will find the next article, a never-before-published tale with equally unique images, heading your way within an hour or so!

So, check your email inbox or, just in case, your spam file.

This next article, which you’ll receive today, was inspired by two lengthy personal histories from women who lived during the Victorian and Edwardian eras. These never-before-published and authentic tales describe a family’s travels by covered wagon on their journey into Indian Territory, 1895-1901.

Then, following that and in about 2 weeks time, there will be another new and true story about the same family’s neighborly relationship with Frank James, the notorious train and bank robber who was second-in-line within the infamous Jesse James Gang.

As I said, I can guarantee the truth of these stories and that they are authentic. I know because I inherited these letters and audio interviews. The stories were handed down to me by two exceptionally aged but well-educated and pawky women. These were my relatives as I knew them when I was but a very young child.

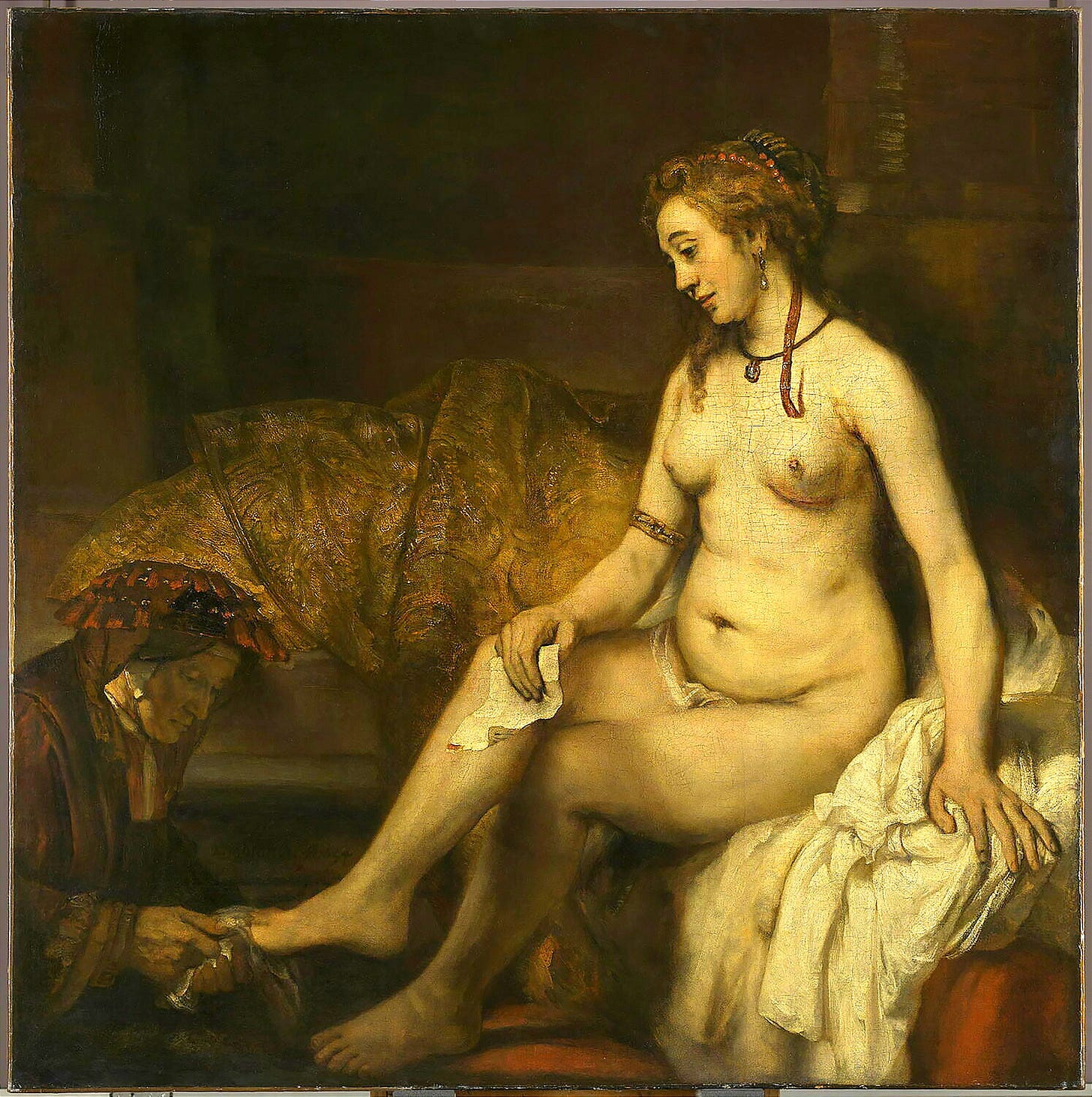

As usual, I’m dedicated to adding new, truthful, scarce, or never-before-published information to every article here at Juicy History. I also strive to include strong imagery that has rarely or never-been-seen-before to help ignite your imagination.

I want historical stories to become vividly alive as you read them. I aim to encourage readers who were initially turned off by history class to reconsider the many fascinating stories from our past.

In my opinion, history should be synonymous with time travel.

I often interview museum curators, historians, and academics to authenticate these stories. I’ve also frequently searched through historical documents, including data from antiquarian books and magazines, historical letters, and even coroner’s reports.

As many of you know, I digitally enhance all those illustrations and images for clarity within Juicy History. In addition to being a published writer, I’ve been a long-time professional photographer and graphic designer, having worked for magazines, trade journals, and newspapers throughout my career.

Retouching historical photographic images and illustrations alone can take hours of intricate work before they are published. I often manipulate the colors and values of individual pixels to achieve accurate results and exceptional focus for my readers.

Copyrights, references, and citations are all added. As a professional member of The Author’s Guild, I strongly support copyright law and always give credit to the original sources.

And so, do look for the next story that will head your way within hours: Part I, In Their Words: Covered Wagon Days 1895-1901.

Part II, the story of Frank James, will be added within about 2 weeks time (I’m still tracking down some of the information).

I promise that these and more upcoming articles will be exciting and pleasant reads! Articles listed in my upcoming work will include more stories about vintage and antique fashions, historical glass and crafts, as well as vintage toys, antiquarian books and vintage cocktail and other cooking recipes. So please stay tuned!

Finally and one more time: I will add another thank you here to everyone for your loyalty, patience, and sincere support.

Thank you.

Thank you!

I wish to thank the many people who have helped me throughout my cancer journey. To list everyone here would be nearly impossible, and I would never wish to hurt someone’s feelings if I inadvertently left out a name. However, you know who you are, and I know too. I will not forget your kindnesses.

I truly appreciated reading this… I had no idea how challenging your life had become. In the short time I’ve known you, I’ve seen a strong, intelligent woman with a wonderfully engaging gift of communication. This has humbled me, because I missed the sheer depth of your challenges. I wish that I may continue to be a good friend, and a better listener…hugs…

Having been through three “pink ribbon procedures” myself I really appreciate your story. So glad you’re back to writing. You have talented voice, whether telling you own story or others.