Diary of a 1920s Summer Road Trip

Nostalgic Reminisces From An Author’s Journal

This is a story that describes a time long past but a time that was not all that long ago.

My imagination conjures up the image of Katharine Anthony lying on a cozy blanket beneath the shade of an ancient tree nearly a century ago. In my mind, she is mid-way through their journey and adding entries to her diary about their 10-day road trip.

Their adventure began when they left New York City and motored through the American countryside to their friend’s pecan farm in Georgia. From her journal, Katharine would create a feature article for one of the most reputed women’s fashion and lifestyle magazines of the time.

Katharine Anthony was a successful, albeit controversial, author. She was born and raised in the South but soon adapted to the Bohemian lifestyle that flourished during the 1920s in Greenwich Village. She openly admitted that her long-range plans did not include any return trips to the South, but this changed when her friend, Aspasia, bought a pecan farm in Georgia and extended the invitation to visit over the summer. Katharine reconsidered.

“Haunting recollections of summer days in the South began to lure me pleasantly. The vision of a luscious red and green watermelon cut open in the shade of a sweet-gum tree near the kitchen door rose invitingly before me. The rare champagne flavor of the May-pop that grows at the edge of the cotton-field and the taste of warm, sweet peaches eaten in the middle of the afternoon came back vividly from my childhood.”

And so, along with her two closest companions, Katharine readied their new Ford for a motoring adventure.

“Our party consisted of three, Serena, who had never been west of Syracuse nor South of Philadelphia and had reluctantly given up her tenth European trip in the hope that she might see a crocodile, is an expert driver and a passable mechanic. My driving is not equal to hers but what I lack in skill I make up in energy. For a long-distance dash, my speed is not to be scorned.

Almost a thousand miles lay before us.

“The third member of our party was its chief asset. She was an Irish terrier named Patty. Patty was taken along, not to protect us from the world as you might support, but to expose us to it. She is an extroverted dog who picks up strangers so quickly that it embarrasses her mistress; Serena thinks that a little more reserve on Patty’s part would be only seemly but the dog easily makes friends without any prejudice as to race, age, color, sex, or creed.”

The plans for their trip were carefully laid out, but the two women and their terrier were hardly seasoned campers.

“As it happened, we had no tent. To stretch out an army cot and heave a sleeping bag on and off the running board is about all that I aspire to.

And, Serena, though she would hate to admit it, is no Sampson.”

“We had heard of the free camping sites for Ford tourists, like ourselves, and had planned to take advantage of them. But we found that the etiquette of these camps required a tent and we were therefore barred.

We had to find a substitute.”

“Wherever we spied a brook or field or grove that looked especially inviting, we drove up to the nearest house and asked permission to camp there for the night. Or rather, it was Patty who asked permission for us

since she had broken the ice and introduced us.”

After so long in New York City, Patty had never been out of doors without a leash.

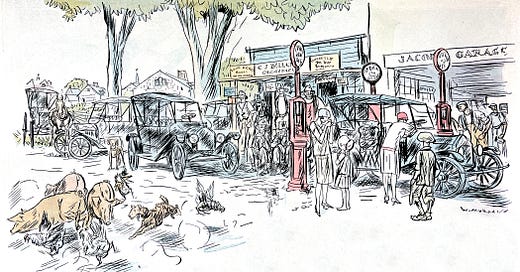

“Now she was a free dog at last. The world was hers, full of chickens to chase, pigs to bark at, crawling babies to lick. While the gas tank was being filled, she bounded joyfully through her domain. Up on the front porch, out through the back yard, down to the horse-lot, back through the store, she flew like a disembodied spirit. By the time she landed again on the back seat and the engine started up, a voice was shouting after us, “What’ll you take for that dog?”

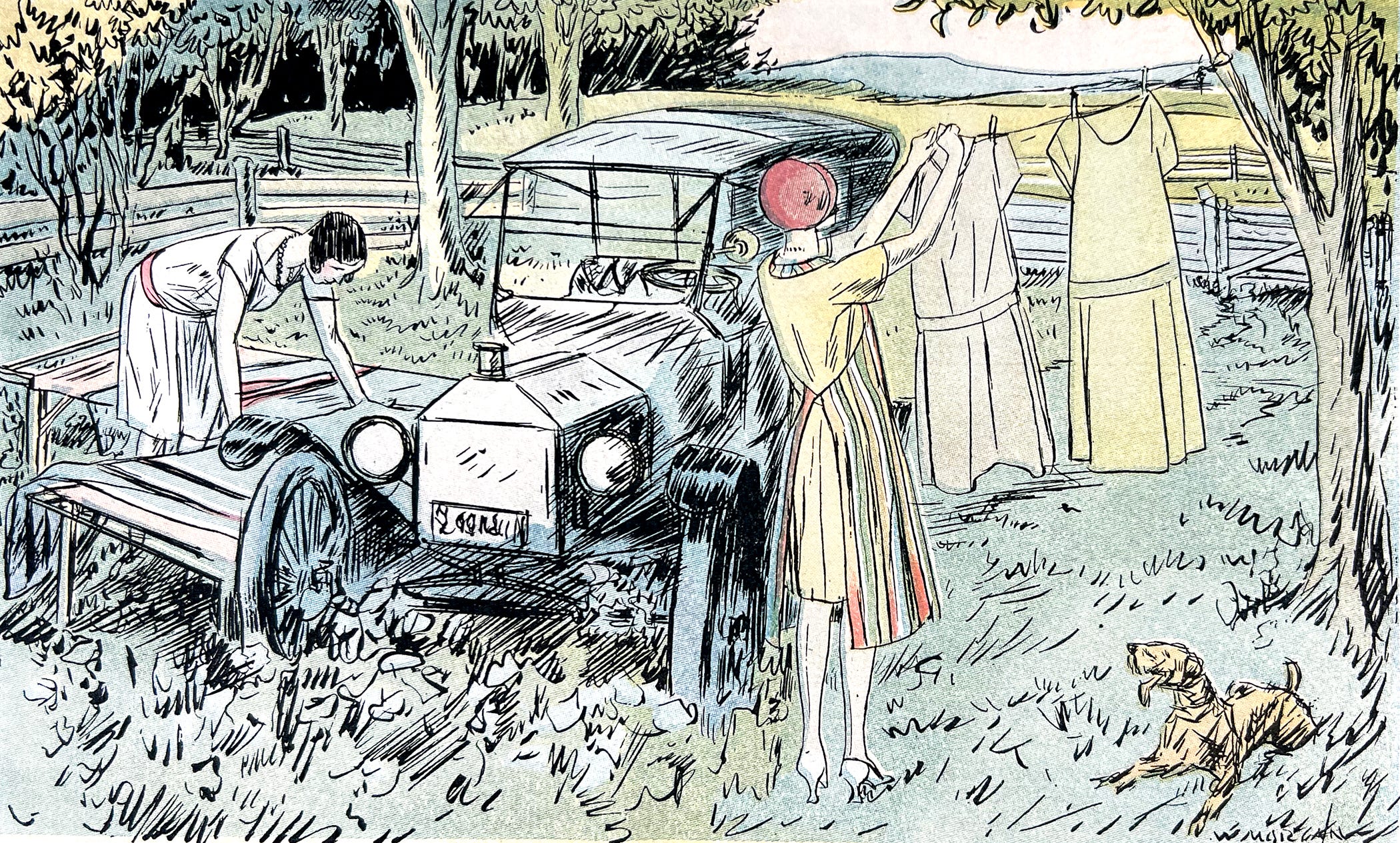

The only clothing the two adventurers had packed included fine silk city attire as well as three cotton and two challis dresses. A bright rainbow-striped kitchen apron completed their travel garments. As the hot summer days sped by, their silks were spared, but the day dresses became their go-to daywear.

“When these garments were washed out in a brook or river and dried overnight on a twine wash line, they looked quite fresh and fine indeed without any ironing. It was sheer luxury when Myrtle Mead, a motherly woman

who lived near the oak grove where we camped one night,

took out her smoothing-iron and pressed my rough-dry pieces for me.”

The most trying of times between the two women came about when their enormous band box filled with Katherine’s fancy broad-brimmed hats took up too much room to travel comfortably. The problem appeared to be solved when they strung the box up with twine across the top of the car over the back seat so that it resembled, as Katharine wrote, a large round birdcage swinging above them.

“But as soon as the Ford began to hit thirty miles an hour, the bandbox began to dance. It jiggled so gayly on its moorings that the string finally wore through and the giddy hatbox landed with a crash in a passing field.”

Eventually, the fashionable women gave up their idea of carrying so many hats. They stopped at a millinery shop along the way and had their precious hatbox packaged up and shipped on ahead to their friend’s farm in Georgia.

Most nights, Katharine and Serena slept tucked into bedding-lined cots, beneath the stars, next to their vehicle which was “hub-deep in Queen Anne’s lace and blue cornflowers.”

“The field was open to the sky. Lying on my canvas cot, I pretended that I was floating in a canoe on a shoreless sea. I dipped both hands into the Queen Anne’s lace which foamed up all around me and gazed straight out into the summer night. The stars seem strangely near when you sleep without a roof. Now and then one of them fell, tracing a thin line of white fire in the heavens as it vanished. Where it went nobody could have told, and nobody could have missed it from the myriads that remained.”

“In the pond at the bottom of the field, the bullfrogs thrummed a symphony. Cellos and bass viols twanged harmoniously together, except for one old artist who struggled with a loose string that he could never tighten wholly to his satisfaction. Not far from us, the pond had an outlet and the sound of water rushing over a dam fell soothingly through the night.

The frogs and the waterfall lulled me at last to sleep despite the watchful presence of the near, unblinking stars.”

Throughout their long journey, Katharine and Serena kept their food with them in a large wooden box that Serena had custom designed and built with her own hands in the schoolhouse woodworking shop. When Katharine first saw the highly polished, enameled green chest with elegant brass handles and padlock, she deemed it too elegant to take on such a trip. Serena scoffed at that idea and insisted that it was just what they required in that it was airtight, designed to fit on their car, and secure. Furthermore, it accommodated two oversized, wide-mouth glass thermos bottles. These were large enough to hold ice that kept butter fresh and even ice cream icy.

And so, the women and their dog traveled over the country roads toward their Southern destination. Along the way, they scouted for signs pointing to roadside tables selling baskets of produce, homemade jams, and honey. Katharine kept a diary entry of the meals that they enjoyed for one full day, including teatime which they often took mid-afternoon.

“Breakfast: Red Southern plums from a farmer’s basket, fresh laid eggs on toast made from salt-rising bread, watercress from the brook that gurgled through our dining room, and coffee.

Lunch: Shrimps broiled in butter, garnished with watercress; young beets and beet-greens boiled whole; potatoes boiled in their skins with a salad of sliced tomatoes and scallions with dry salt. Dessert was fresh peach ice cream from the wide-mouthed vacuum bottle. Spring water.

Afternoon Tea: Hot tea from the other vacuum bottle. Three-quarters of an angel food cake bought from the Blue Bird Tea Room,

and bought for 30 cents without stopping the engine.

Supper: Hot biscuits from a neighbor’s oven, fresh butter from her churn; sweet milk from her Jersey cow; grape jelly from her pantry. This supper was served to us out-of-doors by Mrs. Marian, and her daughter Tish, who came in their white dresses with two trays across the pasture at twilight.

“And for Patty, a quarter pound of chipped beef either fresh or from a tin, garnished with pepper-grass or cantaloupe rinds, dog biscuits and water at every stop.”

Nearly every day, while at the wheel, the friends drove their Ford motorcar over dirt roads under blue skies, and in sweltering sunshine. Their travels were only interrupted once when they were drenched inside their open car by a warm July shower.

“The rain pelted sideways through the car and before we could seize coat or sweater, we were soaked through to the skin. There was nothing for it now but to drive through it and enjoy it.”

But as the women drove through Maryland, they eyed a terrific storm slowly moving across the horizon. The Ford was causing plenty of trouble for them as well, and Katherine wrote:

“We drove through a sunless glare and the radiator boiled like Vesuvius.”

“Serena had taken somebody’s expert advice and had a hole bored in the radiator cap to let out the steam. It worked even better than we had expected. In the wake of the steam came the boiling water

and the car flew along behind a neat little two-foot geyser.

We closed the windshield to shut out the scalding water but the geyser kept on playing against the glass plates. As the dust from the road thickened on the plates, the spray made little rivulets with tributaries which ran down the glass in a complicated pattern. It was very annoying for the driver.”

“I cleaned the windshield until there was nothing left to clean it with. I sacrificed an old silk nightie and then borrowed waste from the gas stations which we passed. It was impossible to keep up with the explosions of the geyser, which gurgled and gasped and spat every time the car increased its speed.”

“The engine itself was all but red-hot. We took off the hood and gave the unsightly thing its freedom. But the outside air was so hot that ventilation brought little relief. Hotter than a kitchen stove, hotter than Tophet,

it turned the inside of the car into a superheated Sitz bath.

We opened the side door wide and fastened it back with a string.

Serena and I had lost all regard for appearances.”

Forced into a long afternoon stop, Serena once again proved her skills as a mechanic and repaired the Ford. All the while, the two women continued to eye the threatening clouds that were slowly approaching.

When they finally clambered into the car again, they drove as fast as they could and tried to outrun the storm that followed them on their way toward Baltimore. But the skies grew close and blackened once they reached the small town of Perrysville. Serena scrambled just in time to pull their vehicle into a deserted lumberyard with an open garage, just as the clouds exploded.

Torrents of rain, with what Katharine described as egg-sized hail stones, bombarded the building with a corrugated iron roof; the women could not begin to hear one another speak. The winds howled and a nearby steam soon flooded its banks. The low-lying land around them filled with water until their protective garage succumbed to the deluge and the Ford’s tires were nearly submerged.

“Serena, who thinks her car the best in the world,

remarked that it had but one defect:

it did not float.”

There was nothing left to do but wait it out, and the women curled up on the seats of the Ford, with Patty on the rubber mat next to Katharine in the back of the car. They slept for hours through the remaining downpour until just after dark when Patty barked ferociously at a local fellow and his dog, as well as a police officer who followed along soon after. The men were out assessing storm damage and the cloud burst, they agreed, had washed out all the surrounding roads. They promised, however, that all should be clear and dry by morning.

By then, the water had adequately subsided from the garage floor and the officer guided the travelers inside their car on down to the local hotel. The owners served coffee and sandwiches that had been prepared for the volunteers who were gathering to clear the roads and the women took a room, which Katharine described as delightfully new, clean, and with a private bath. There was even space enough for a tub in which to wash their muddy four-legged companion.

After a good night’s rest, Katharine, Serena, and Patty headed off again through Maryland and sped over the countryside lined to the horizon with golden wheat fields. They raced across the picturesque Shenandoah Valley and soon reached the smooth, red dirt roads of North Carolina. Katharine described their growing impatience to reach Georgia, especially after nine full days on the road. And she noted that night after they reached Georgia’s state line:

“Cotton, on both sides of us, something magically green opened out. Young cotton, still virgin green, without blossoms on it. Acres and acres of cotton plants stretched away, out of sight, in long curving rows, planted so to break the force of the rain wash on the sandy soil. The green plantation went on and on, with never a fence to mark a line or vary the crop. We were in the South.”

“At breakfast the next morning, the waiter beamed upon me when I asked for the molasses. People who travel in cars with New York numbers usually prefer maple syrup or orange marmalade. The waiter put the silver pitcher on the table with a flourish of pride.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, “the very best. Georgia cane. Buttermilk biscuits? Yes, ma’am. It’s hot rolls on the bill. Dogs not allowed in the dining-room. Under the table? Yes, ma’am, certainly. You’all goin’to Athens? Sixty-eight miles. You’ll be there befo’ evenin’.”

The trio set off again and by noontime, they came upon a shopkeeper sitting on his porch. Knowing they were close enough, they asked for their friend Aspasia by name.

“Just cross the creek and the branch,” he called, “and go on up the hill.”

“And there it was as he had said: a low white house in a grove of young pines with a red chimney peeping out above the green tops, and Aspasia in an orange-colored dress running out to meet us.

Past the white letter-box and up the driveway through the cotton patch, the Ford whizzed at last among the young evergreens. While Aspasia threw her arms about us, Patty ran up the path and leaped upon the porch. From the threshold, she barked a joyful welcome to the three of us.”

“Come in,” Aspasia said. “This is where I live. This is my castle, my new world. Sit down and make yourself at home.”

This excerpt from the magazine article written by Katharine Anthony was published in Woman’s Home Companion for the July 1926 edition. Katharine was a popular author during the first half of the 20th century, and was known for her feminist, psychoanalytic biographies of famous women including Louisa May Alcott, Catherine the Great, Queen Elizabeth, and her relative Susan B. Anthony. She was a suffragette, a Freudian, a pacifist, and a champion of women’s rights and child welfare. Katharine Anthony lived and thrived as a feminist in Greenwich Village during a time when Bohemian ideals were burgeoning.

Her life partner was Elisabeth Irwin, founder of the progressive Little Red School House. Together they lived in The Village for three decades and adopted several children. The women never openly discussed their personal relationships and simply referred to themselves as “unmarried.”

But there is more to this story than what Katharine divulged. Serena was actually Katharine’s life partner, Elisabeth Irwin, and they went to Georgia to meet up with their new friend, Jeanette Rankin. By then, Jeanette was the first woman to be elected to the United States Congress (in 1916). For this article, Rankin was given the pseudonym Aspasia and was a lifelong friend to both women. After Elisabeth died in 1942, Jeanette became an especially close companion to Katharine until Anthony’s death in 1965.

What a most delightful article I so enjoyed these latest writings from Julia, and I am so excited for the next article. Can't wait!